Female Hands at Work An interactive exploration of 3 women artists and their impact on contemporary Sifnian potteries

Assembling an archive of the traditional ceramic workshops of Sifnos will perpetually remain an unfinished cultural excavation, as well as an open-ended invitation. To date, the Archipelago Network’s remarkable collection of images and recorded voices not only illuminates a deeply rooted and complex craft-centered local lifestyle, it urges us to spot lacunae and seek out missing fragments of an ever-expanding archival whole.

Inevitably in a patriarchal country like Greece, the prominent voices representing the island’s family-owned cottage industries are the gifted Sifnian men who own their family businesses. They constitute the protagonists featured in Archipelago Network’s video portraits. Viewers quickly sense they are witnessing, to quote the ubiquitous musician James Brown, a “man’s world.” And yet, if we listen attentively to these potters’ testimonies, and closely examine the historical photographs and film/video footage, we recognize that Sifnian ceramic workshops are neither individualized nor exclusively masculine endeavors. Rather, they operate as collective enterprises. Women—both family members and outsiders who arrive to collaborate with local ceramicists—have played central roles in evolving these Cycladic craft traditions and ensuring that they remain vital.

Introduction Gendering Sifnian Potteries

In the 2020 Bulletin report prepared by Lydia Koptsopoulou and Maria Komi for UNESCO’s National Intangible Cultural Heritage Index–which formally registered Sifnian ceramic tradition in January 2022—the authors trace the history of gendered production and the infusion of women’s contributions to the pottery workshops. They noted that before the 1950/60s, most traditional potteries were located outside of the island’s village settlements, “with the result that women were solely responsible for the organization of their households and men were left alone in the workshops, as long as necessary.” It was common for men to work from Mondays through Saturdays, only returning home to their families for one day a week. Once the island’s villages began to expand in the second half of the 20th Century–or, conversely, when some workshops re-established themselves within settlements–women began to take a more active role, as evidenced in many of the Archipelago Network’s historical photographs. As Koptsopoulou and Komi explain,

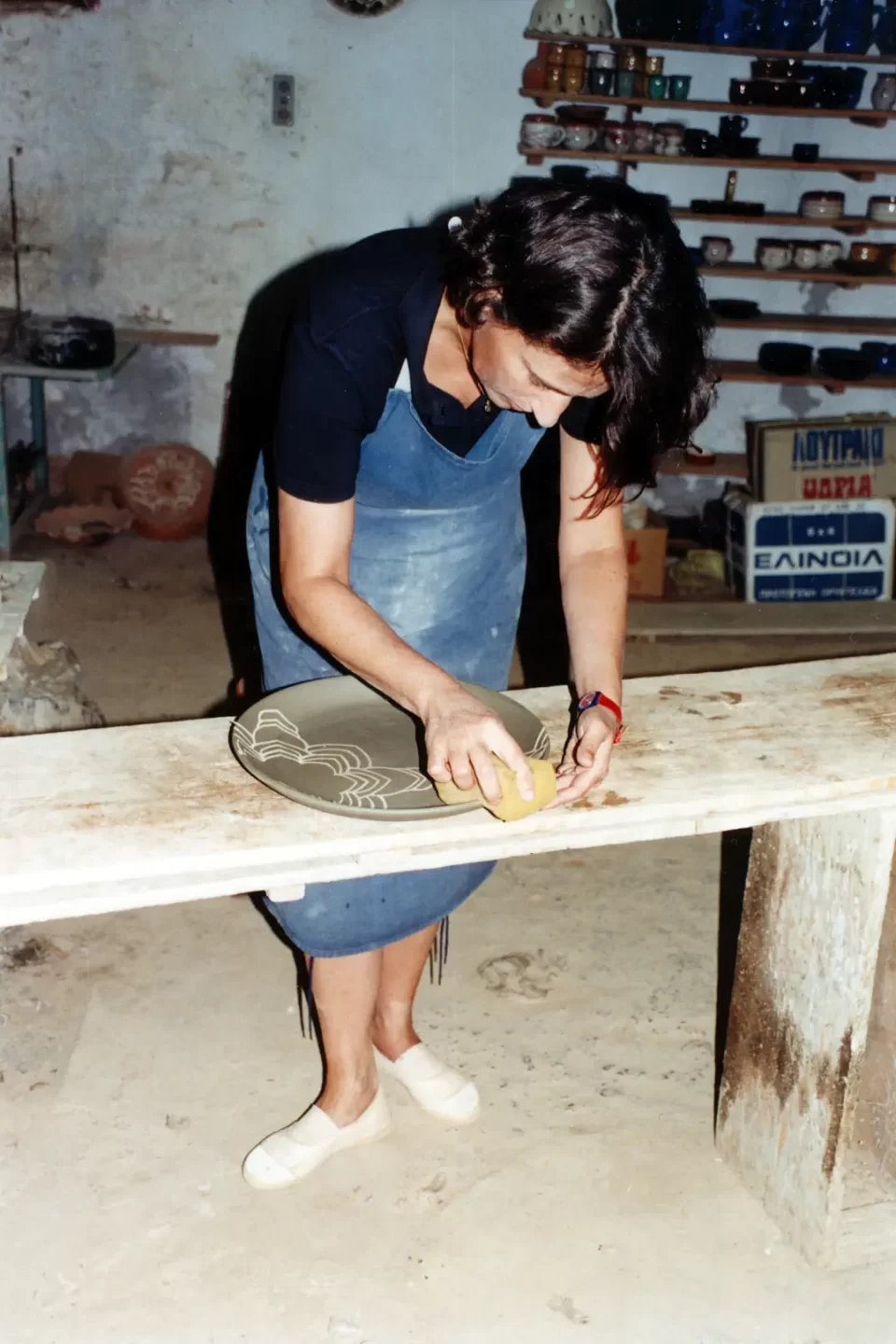

“Women initially helped with minor tasks, such as transporting the ceramics from the workshop to the kiln, after which they were loaded onto boats to be sold in other areas. Women’s involvement is increasing with the increase in demand for ceramics in the context of the island’s tourism development. The need to make elaborately decorated ceramics led potters’ wives or daughters to undertake the work of decoration.”

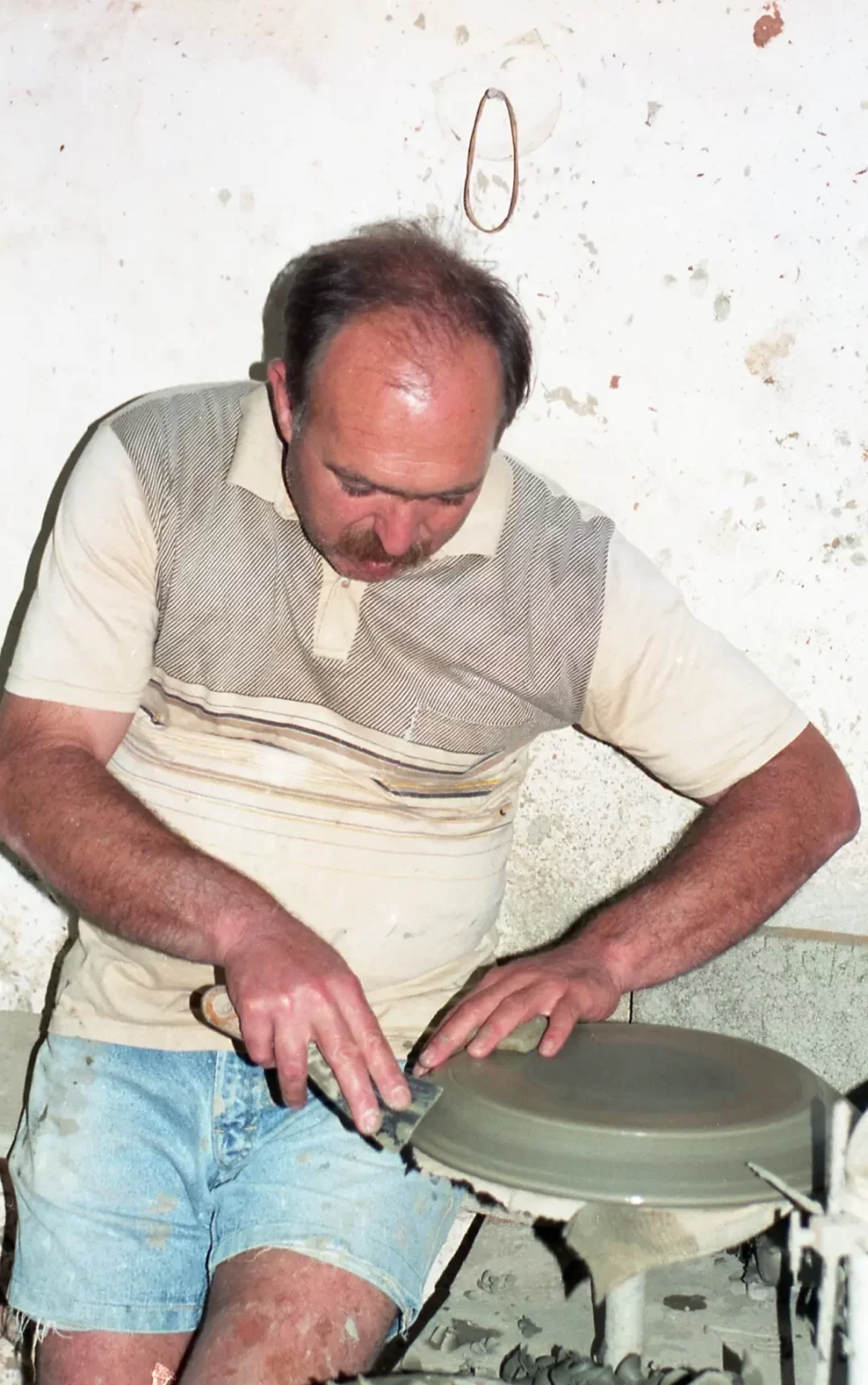

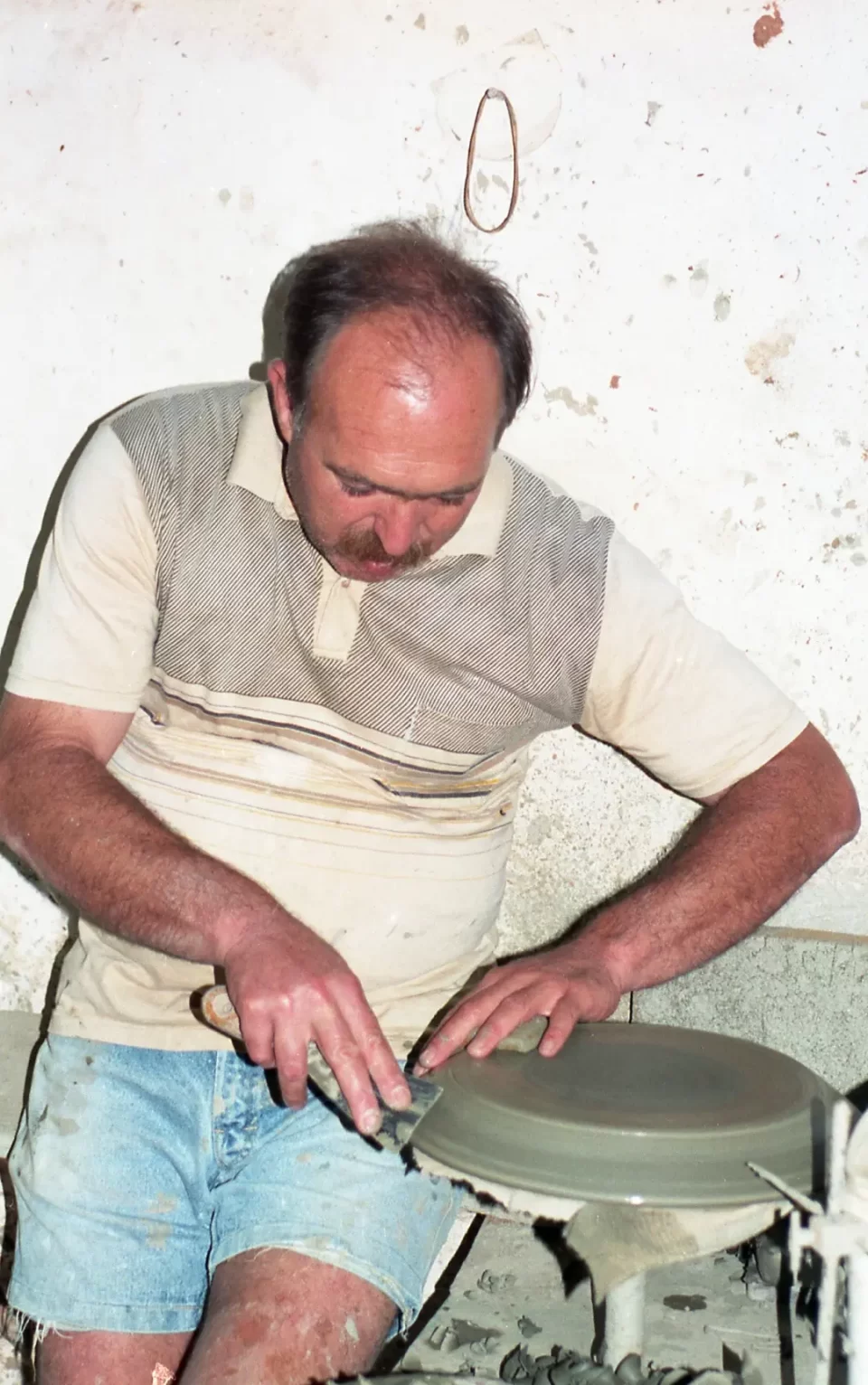

Frequently, gender schism in the traditional ceramic studio has been characterized as binary: men sourcing clay/ working at the wheel vs. women embellishing ceramic surfaces. This suggests these may be fixed primary and secondary roles. But this implicitly hierarchical stereotype is not entirely accurate. It’s true that Sifnian men labor long hours generating pots using the haptic knowledge passed down between grandfathers, fathers and sons (and sometimes between uncles and nephews who become their apprentices.) But these days, more often than not, male potters do not entirely replicate their ancestors’ methods: many increasingly turn to commercially available, imported clay and employ electric vs. fire-stoked kilns, thus saving themselves much of the backbreaking work previous generations had to heroically endure. In some cases, male workshop members also enjoy decorating the surfaces of their own and others’ works, recognizing that the formal shape and glaze treatments have equal importance in determining the success of a pot. Moreover, it’s important to note that women, along with men, have profoundly influenced the look and character of a pottery’s wares, as well as their business profits. As we will explore later in this essay, women such as Zoe Keramea, Diane Katsiaficas and Kateh Lembesis have catalyzed the collective imagination of the family potteries they work within, each demonstrating a unique aesthetic sensibility informed by distinct forms of knowledge and intellectual curiosity. For the past quarter century, they have each expanded the Atsonios and Lembesis workshops’ visual repertoire, including the very shapes that the men create on the pottery wheels.

“Come to the pottery this afternoon”: this is the preferred use of the local term “pottery”. It describes a many-handed, multi-generational and multi-gendered production space–and not just the ceramic objects generated within. Potteries are familial and social spaces where aesthetic exchange and ongoing re-invention—artistic and personal—takes place. Stories, local gossip and periods of concentrated silence all circulate as the local soundtrack while the pottery’s objects are crafted. The work rhythm comes to a halt when lovingly prepared, home-cooked lunches are offered and shared, often complemented by laughter and glasses of home-brewed tsipouro. Children, visitors and pets frequently enter the space, eager for attention or looking to create something of their own. Sifnian potteries, therefore, are best understood as dynamic, site-specific social and creative networks of exchange. Each harbors their own intangible cultural character, dialogical atmosphere and ethos, operating through genealogical connections, friendships, and unpredictable encounters.

In addition to being spaces of communal dialogue and sharing, Sifnian potteries are simultaneously popular commercial spaces, increasingly operating as a magnet for the island’s expanding tourist industry. On a daily basis, curious visitors to the island, international art collectors and business representatives knock on the potteries’ doors, requiring that foreign languages be navigated and stories be told about how and why things are made in the studio. Monies are exchanged and new commissions get proposed and considered. This lively give-and-take frequently results in emergent formal possibilities: might a commission for a hotel table setting or a birthday, for example, become a catalyst to create a fresh design? Such encounters with visitors and clients frequently shift the course of the pottery’s production, while also augmenting its professional reputation and the financial livelihood of its entire work force.

To provide examples of the feminine, communal and transactional aspects of today’s potteries on Sifnos, my focus will be on the aesthetic and cultural influences of the three remarkable women mentioned earlier. Zoe Keramea and Diane Katsiaficas were originally “foreigners” to Sifnos, but have since established a periodic yet sustained collaboration with local potters—an ongoing friendship and creative exchange lasting 25 years. Keramea continues to collaborate with Antonis Atsonios in the seaside town of Vathy, while Katsiaficas works within Lembesis’ studio in Agia Anna, a tiny village adjacent to the large settlement of Artemonas. The third figure, Katerina (“Kyria Kateh”) Lembesis, was the beloved mother of Giannis and “yiayia” (grandmother) of Nikos Lembesis. She befriended Katsiaficas in 1999 and the two women subsequently collaborated closely to develop the pottery’s signature style of colorful glazes featuring dynamic images of flora and fauna. As we will see, Kateh Lembesis earned local celebrity status because of her wildly imaginative artistic talent; she remains the spiritual heart of her family’s pottery, despite her death in 2019.

Watch “A Woman: Kateh”, a short documentary film about Kateh Lembesi made by artist Eleni Tzirtzilakis in 2018-2020.

Wherever possible, these three women will “speak for themselves” in this essay through hyperlinked audio files of interviews (several made during the summer/fall 2023) and through photographic, video and printed materials gleaned from personal archives that the artists and their family members generously shared with me. Click on these hyperlinks to dig deeper into these women artists’ personal narratives, which augment their influence on– and experiences with– ceramic production on this Cycladic island.

Overlapping Origin Stories

While there are, of course, other women of note who have also contributed to Sifnian potteries over the years, Zoe Keramea, Diane Katsiaficas and Kateh Lembesis are uniquely poised to be among the first women featured in Archipelago Network’s expanding archive for several reasons. The story of how they became so embedded in the life of local potteries, both as “outsiders” and “insiders” on the island, points to the profound value in developing cross-cultural artistic exchanges between contemporary artists and traditional artisans, which can greatly enhance the artistic imaginaries of all parties involved.

Keramea and Katsiaficas are of Greek descent, although Katsiaficas was born abroad. Unlike Lembesis who lived on Sifnos for her whole life, these two multi-media artists were raised and educated in various urban environments. Their professional training amplified their deeply cosmopolitan perspectives, yet they remained intimately aware of Mediterranean history and local culture. Establishing homes in both the United States and in the Attiki region of Greece, each artist cultivated a hybrid existence straddling these contrasting worlds (Zoe in New York City and in her family’s home in Paleo Faliro, Athens; Diane in Minneapolis, Minnesota and Kokkino Limanaki, Rafina). Before starting to collaborate with traditional potters in Sifnos, both women had active art careers and exhibited regularly in an international contemporary art scene. They continue to share a passionate commitment to doing intensive research as a means of crafting their materially-oriented works, which have been featured in major cultural venues throughout the USA, Greece, China, Iran and Australia.

Their artistic sensibilities differ significantly: Keramea manifests the precise modular logic of a poetic yet meticulous mathematician whereas Katsiaficas takes a more spontaneous, lyrical and painterly approach to making her historically-grounded analog and digital works. Nonetheless, their life trajectories have echoed one another’s in other interesting ways. Keramea completed her Meisterschülerin Degree in printmaking at the Universität der Künste in Berlin in 1981–the city where Katsiaficas had been awarded a DAAD Fellowship to study the resurgence of German Expressionism and research handmade papermaking processes just four years earlier. Additionally, both women benefited from nearly simultaneous Fulbright Foundation Fellowships to cross the Atlantic Ocean in opposite directions. The award enabled Greek-born Keramea to reside in New York in 1989 while researching her new intaglio printing technique, i.e., two stage intaglio matrix prints –zoetypes–while Katsiaficas’ 1990 Fulbright Grant provided a respite from her position as Professor in the Department of Art at University of Minnesota to work in Thessaloniki. There, she focused on investigating the narrative structures of Byzantine frescos. Coincidently, at the time of their Fulbright awards, the artists were both actively exploring the relationship between 2D and 3D forms, using paper as their primary material.

To understand their distinct artistic practices and broader conceptual interests: see Zoe Keramea’s website and this informative text by Els Hanappe accompanying Keramea’s 2012 project with Siakos.Hanappe House of Art; also see Diane Katsiaficas’s website and a 1992 interview with the artist.

Unlike her counterparts, Katerina (Kateh) Lembesis’s education was gleaned on the island of Sifnos. She nurtured her distinct forms of folk knowledge through working the land and sustaining her family and their pottery, while always maintaining an exceptional openness to cultivating community ties and exploring new artistic possibilities, both by painting on ceramic pots and with watercolors on paper.

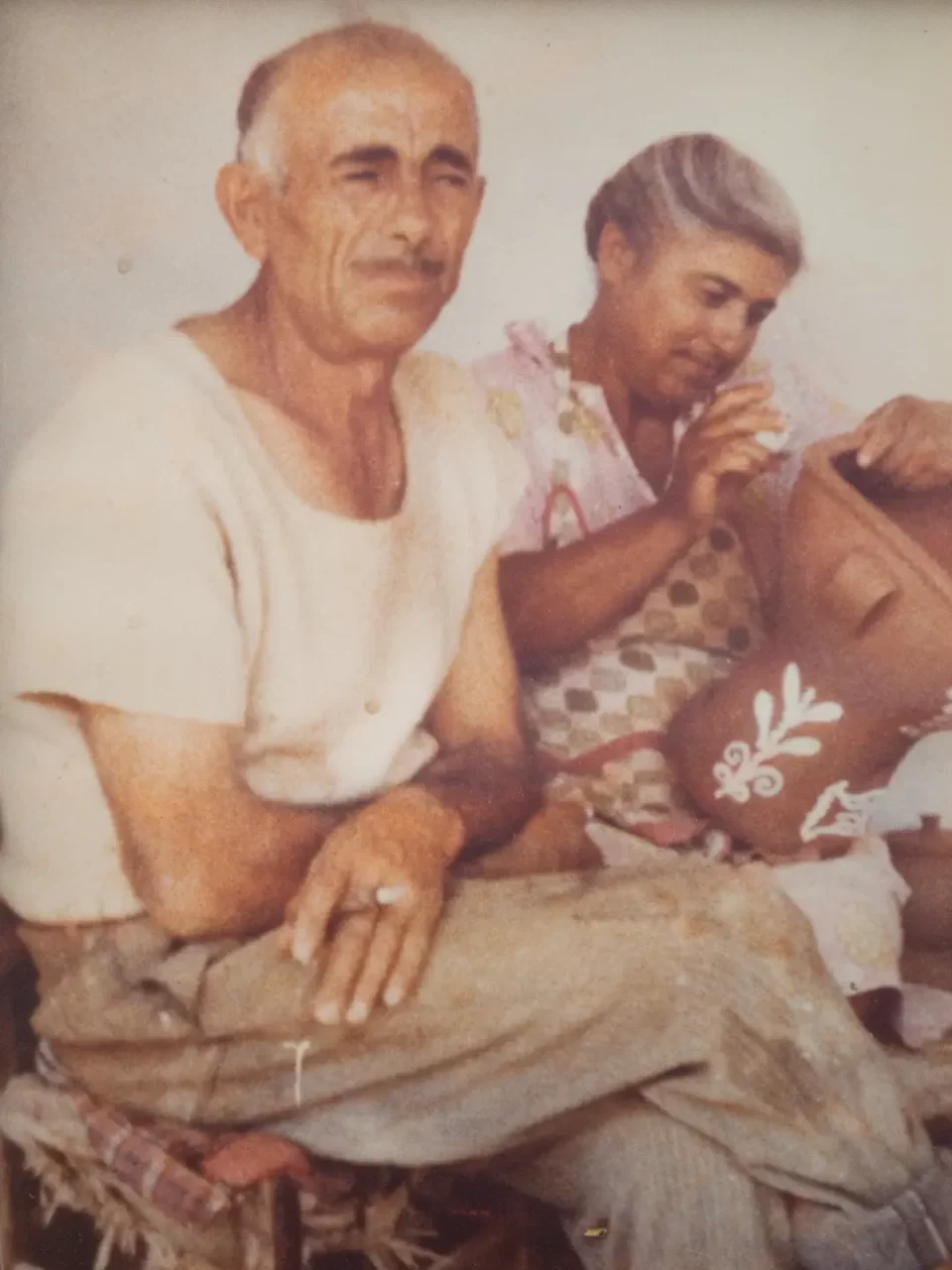

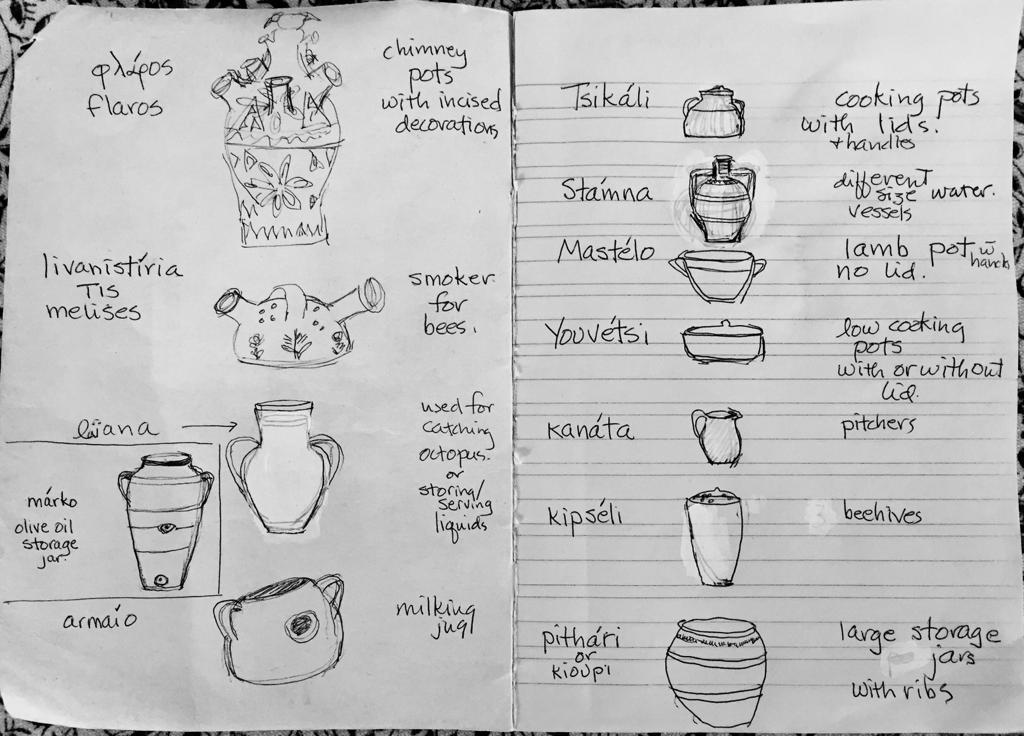

Married to her husband, Manolis, in 1950, they based the Lembesis Ceramic workshop in the seaside fishing village of Cherronisos, where the family worked tirelessly with their three children during the winter months to garner and hand-process clay from the local landscape. During the rest of the year, they used the prepared clay and liquid slip to create traditional vessels for the kitchen such as the tsikali, mastello, youvetsi, foufou and stamna–the centerpieces of their ceramic business.

Kyria Kateh not only painted traditional decorations on these ceramic pots, she used them to prepare the family’s meals. Each ingredient required acquiring its own form of mastery: pressing the olives each October using their traditional stone mill in the settlement of Artemonas; hand-crafting salt-cured manoura cheese; tending garden vegetables and foraging aromatic herbs; kneading bread to bake in the hearth; and butchering animals–a skill that she had learned from her father so that her culinary craft could include meat dishes. Despite the difficult conditions which characterized island life before the advent of paved roads and electricity, at the end of a work week Kateh Lembesis welcomed friends and workers–including sponge-divers and fishermen who worked nearby—all of whom were drawn to the culinary tastes, comradery and family musical talent that she fostered in her home. In an excellent 2006 video portrait produced by Professor Thomas Lane–one sponsored by the Regents of the University of Minnesota and facilitated by Diane Katsiaficas–Kateh Lembesis is seen holding a photographic portrait of her deceased husband. She lights up when describing their life in the pottery: “in Cheronisos we may have been poor but it was a lively time and we always worked with songs and smiles—it was very hard work but we lived well.

These intimate gatherings continued after her husband Manolis died and when her son Giannis moved the family pottery to Agia Anna in the 1980s. There, Kateh continued to decorate the surfaces of the thrown pots, as well as act as the “glue” of the pottery: cooking meals, singing traditional songs, writing poems that resemble the rhyming couplets of Cretan mantinada, cleaning the studio, offering occasional haircuts to relatives and friends, and charming visitors with her unending passion for ceramic ornamentation.

After meeting Diane Katsiaficas in 1999, Kateh’s tendency to paint only iconic, frontal images with white slip on the clay’s ochre surface began to expand. Katsiaficas exposed her to alternative ways of representing flora and fauna in historical source materials. The two developed a profound friendship. We will explore this dynamic creative dialogue and its mutual artistic impact more fully below.

Listen below to Diane Katsiaficas describing Kateh Lembesis cooking for the pottery.

And here, see an interview conducted by Iro Keramida with Kateh Lembesis in You Are Here Magazine (published annually by in Sifnos by Free Press, 2015), where she describes her home and creative life as a painter on ceramics and on paper.

The 1999 Fyrogia Monastery Exhibition

Because of their deep connection to Greece as well as contemporary art practice, Zoe Keramea and Diane Katsiaficas had already met by the time they were both invited by artist/gallerist Popi Krouska to participate in a seminal curatorial project at the Fyrogia Monastery on Sifnos entitled “Fyrogia 1999: An Exhibition of Eleven Artists Working in Collaboration with the Ceramic Workshops of the Island”. Krouska’s personal interest in working with clay, coupled with her deep love for the island of Sifnos, inspired her to propose bringing compelling contemporary artists—most of whom did not have prior experience working with clay—together with local traditional potters to collaborate on preparing an exhibition at Fyrogia.

Krouska chose to include Keramea and Katsiaficas since she had become familiar with their work through her Thema Gallery (a space previously named “Popi K”), located in Athens’ Kolonaki neighborhood. It was at Krouska’s gallery, in fact, where the two artists originally met before getting to know one another more by working together on the 1998 Essential Bonds: 50 Years of Fulbright in Greece exhibition. In consultation with the artists, Krouska paired the collaborative teams of artists/craftsmen, who then began to envision and fabricate objects they would later install in various spaces within the Fyrogia monastery and in its adjacent ruins. Participating artists in this 1999 exhibition included Dimitris Christidis, Niki Kanagini, Ingrid Fragantoni, Diane Kasiaficas, Zoe Keramea, Haris Kontosfyris, Popi Krouska, Yiannis Michas, Minos Orfanos, Katia Roka, and Angelos Skourtis. The local potters who partnered with these artists included Yiannis Apostolidis, Antonis Atsonios, Yiannis Depastas, Yiorgos Exylzes, Frantzescos Lemonis, Yiannis Lembesis and Yiannis Podotas.

Keramea and Katsiaficas crossed paths again while installing the Fyrogia installation, which ultimately led to establishing ongoing collaborations with their local counterparts from the potteries.

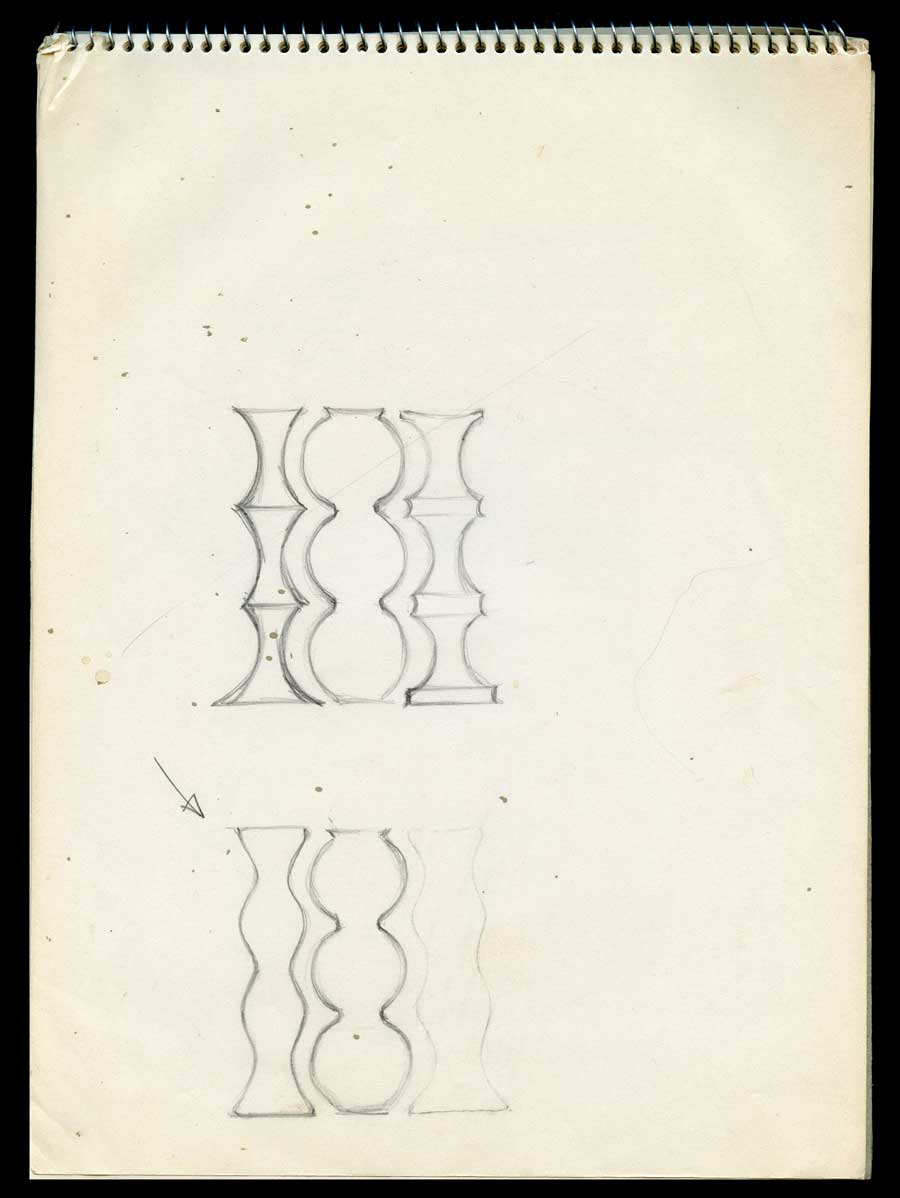

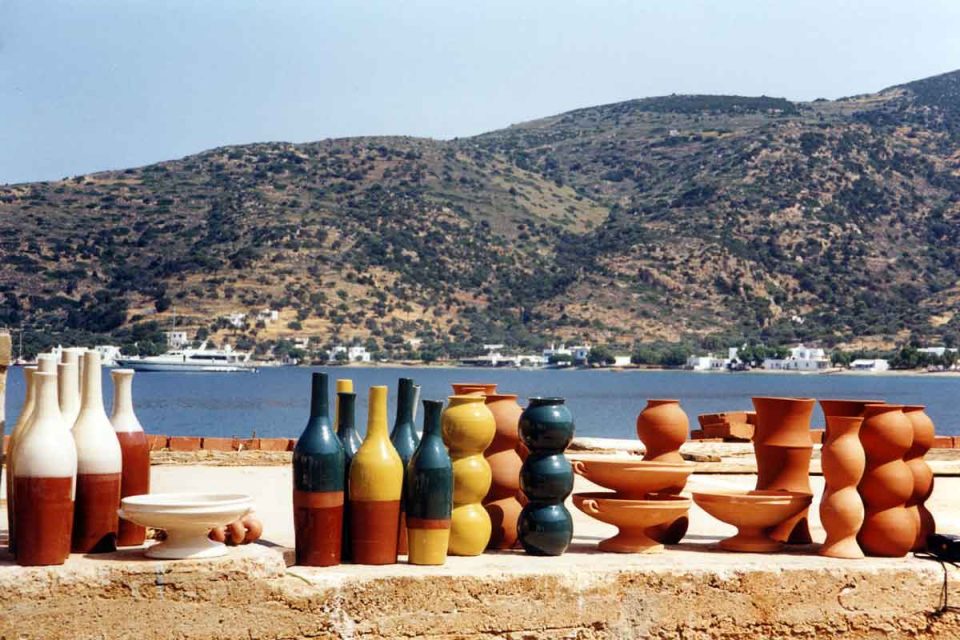

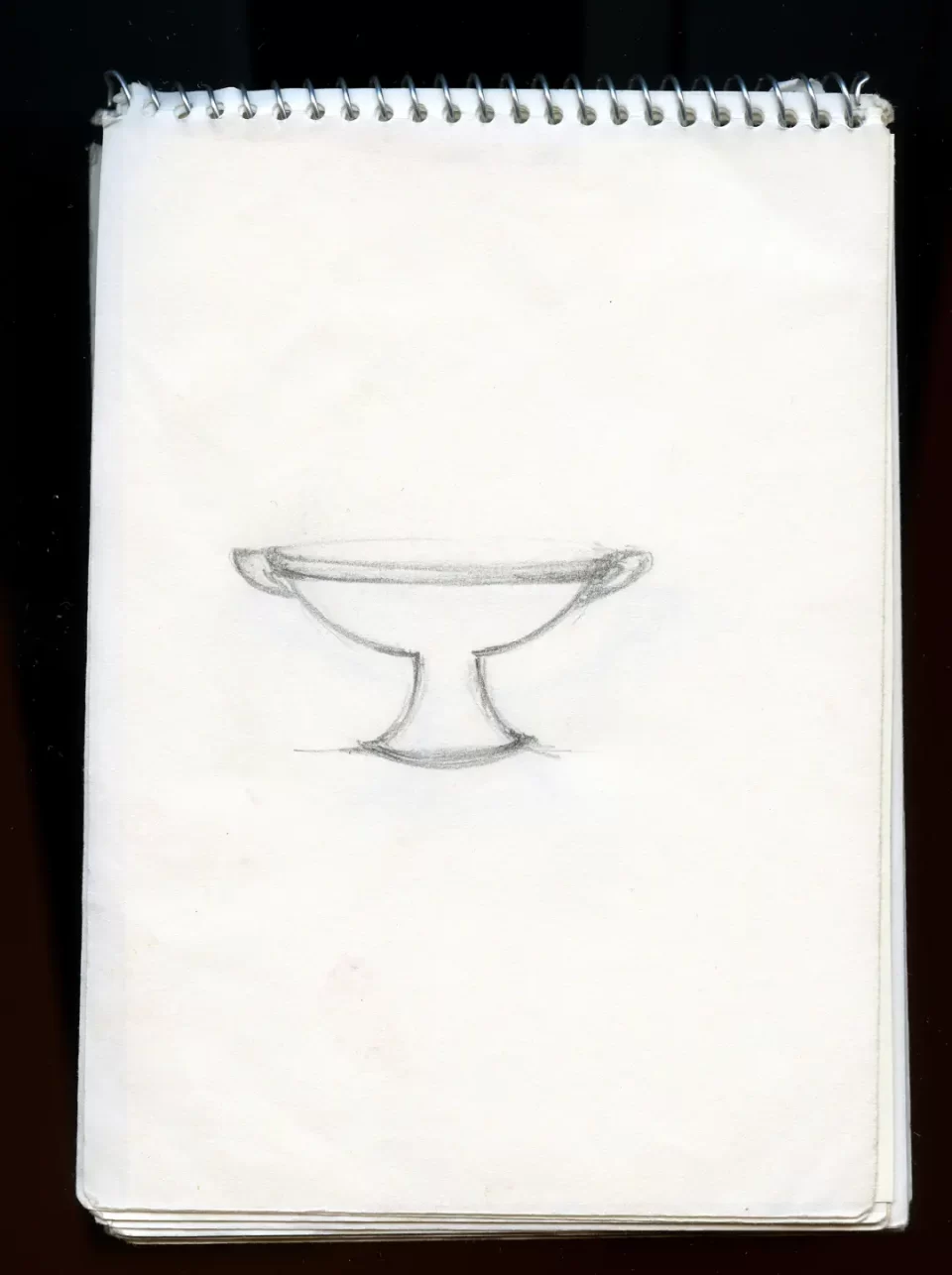

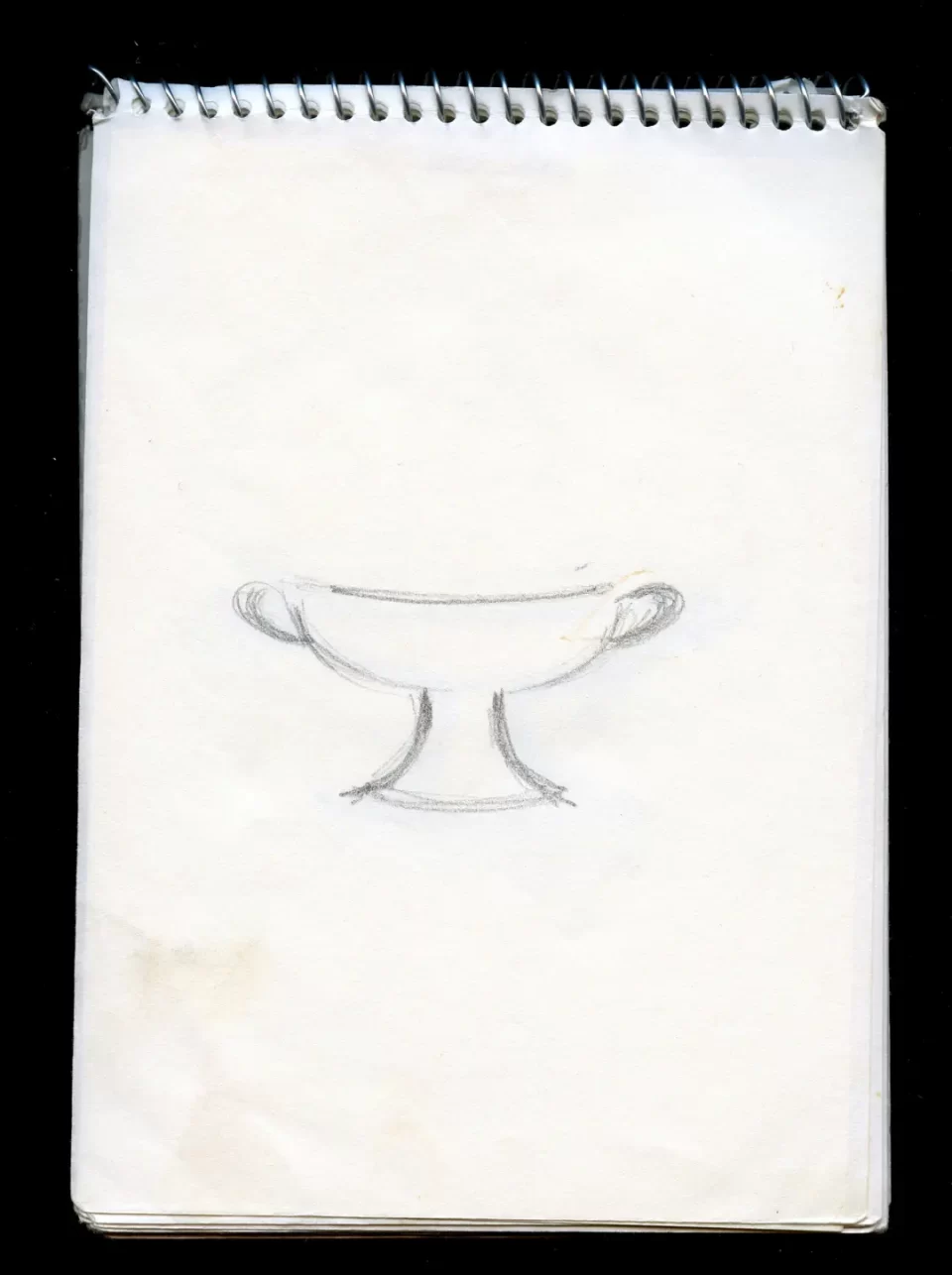

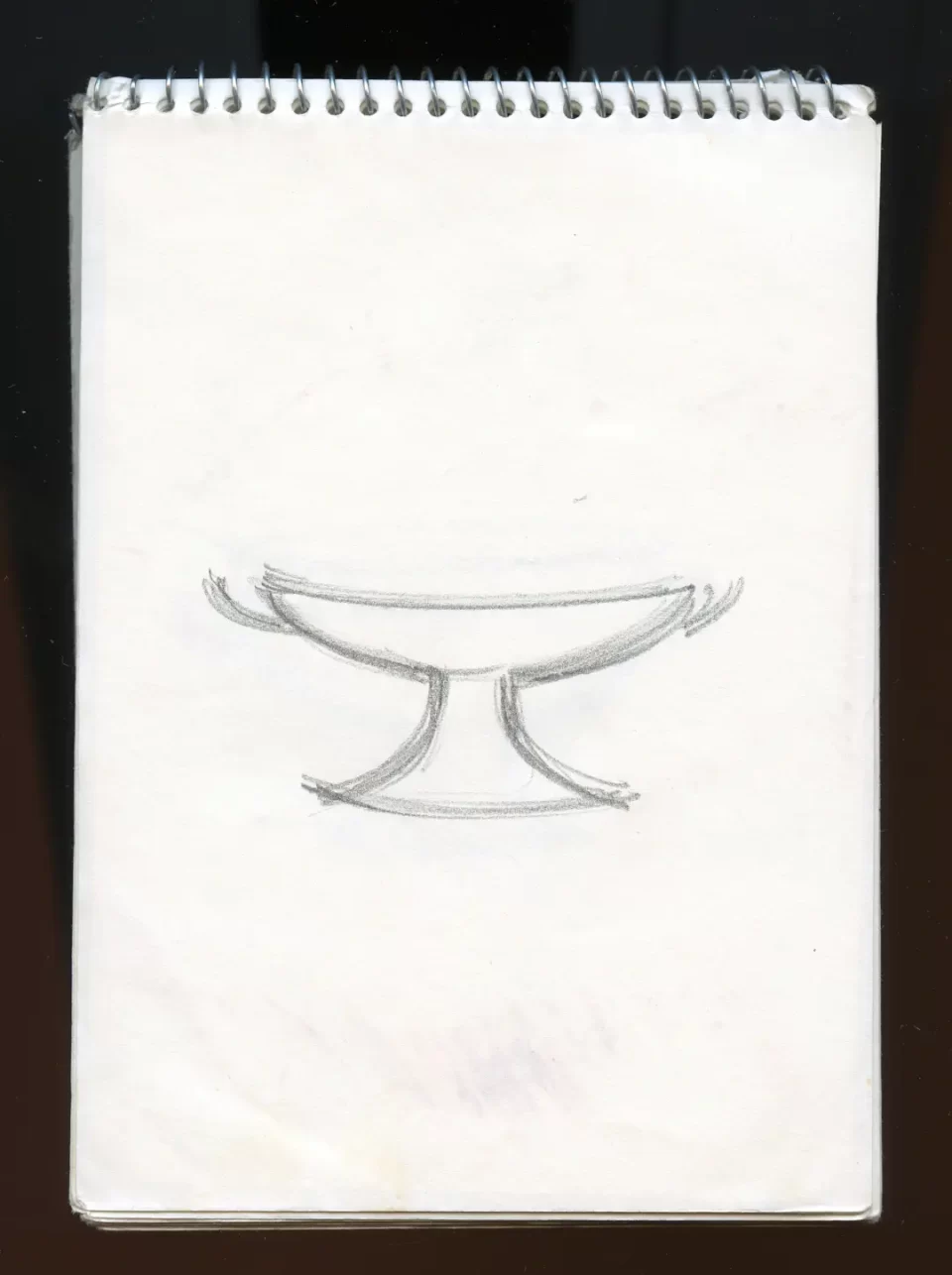

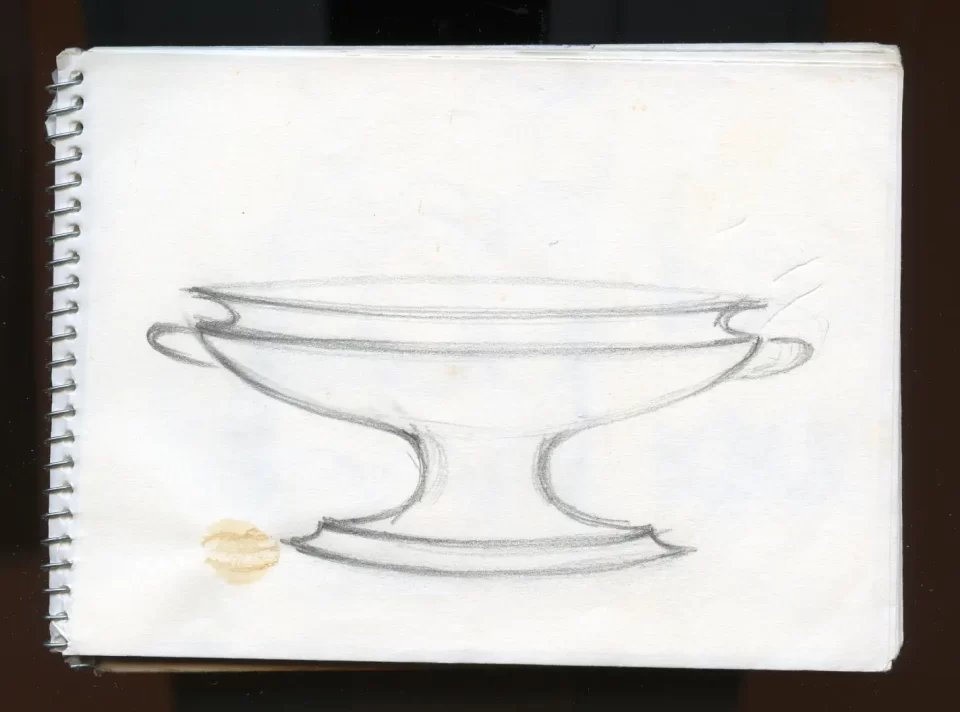

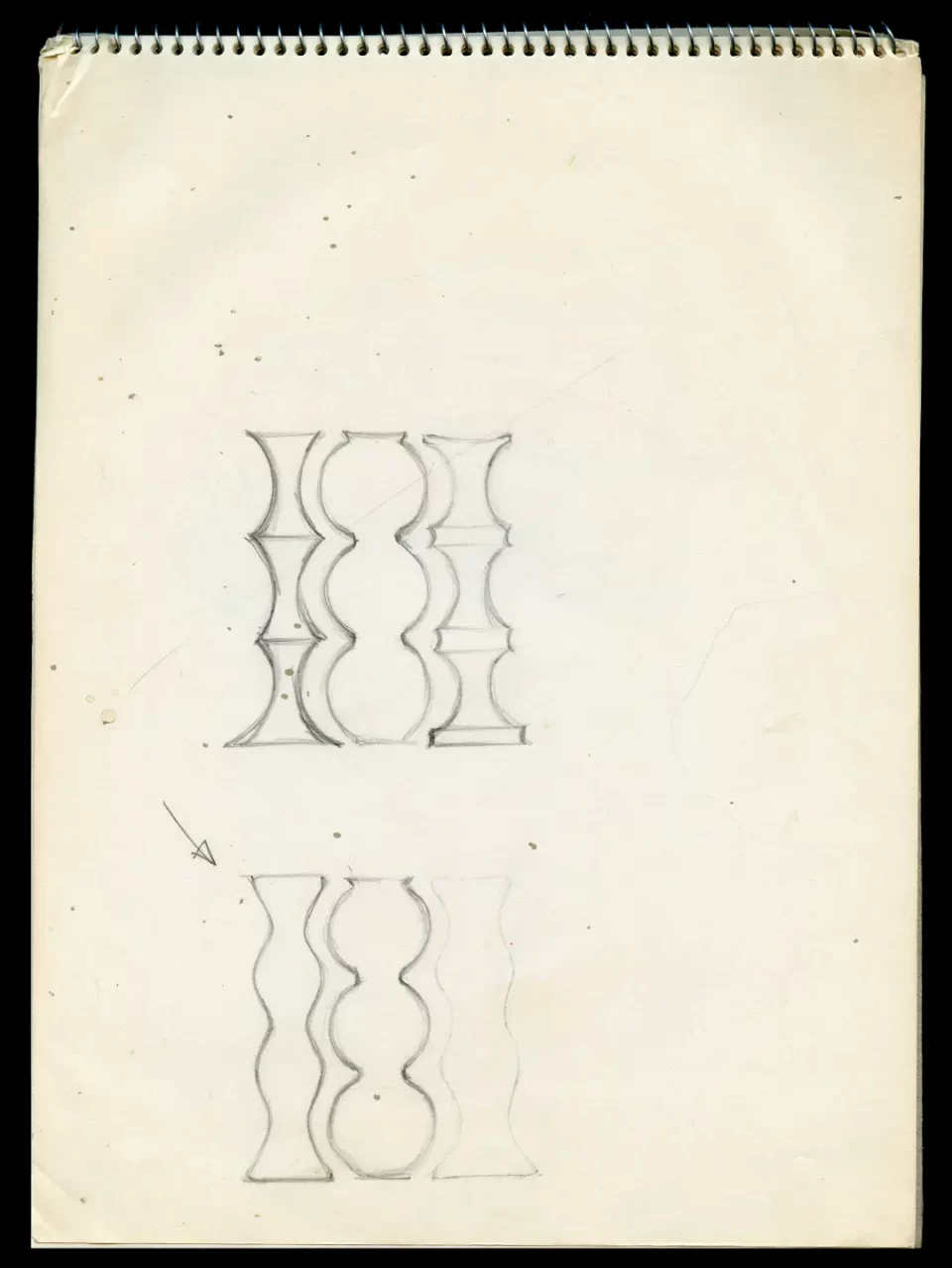

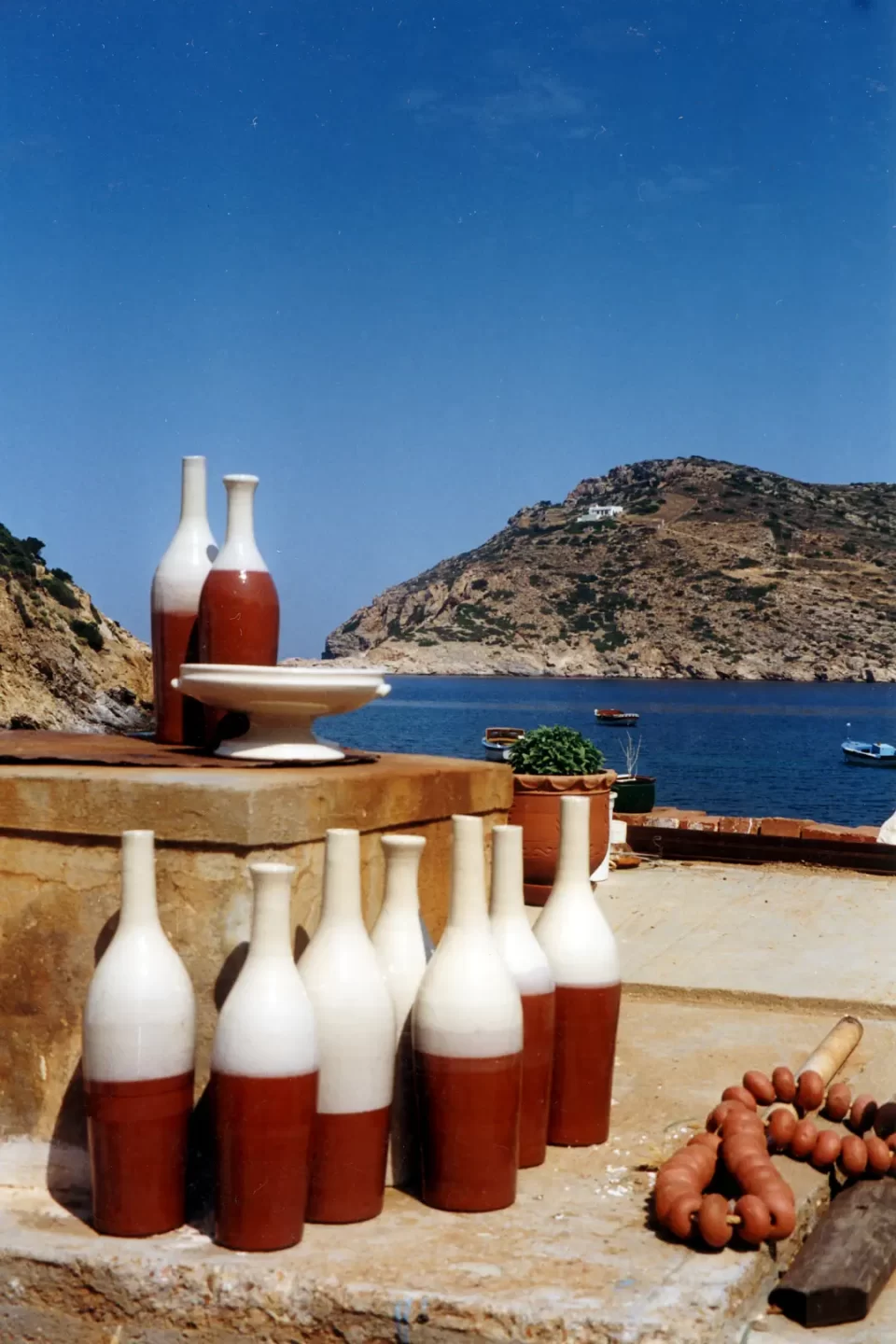

For the 1999 Fyrogia exhibition, Keramea collaborated with Antonis Atsonios to fabricate a series of forms that included kalyx-shaped fruit bowls, twice-dipped bottles, candlesticks, and two varieties of modular sculptures (one loosely resembling a caterpillar with three rounded forms, and the other a bamboo stalk with concave surfaces.) Keramea showed Atsonios sketches of the forms she wanted to make—none of which he had ever crafted before. Atsonios threw the shapes in three parts and later fused them together into a singular whole, in keeping with the modular construction that Keramea had been regularly practicing in her prior works. Also, in a nod to the sacred site of the monastery where the pieces would be featured, these forms subtly echoed the sacred trinities within Byzantine theology, and the candlesticks evoked the presence of fire as part of the Orthodox rituals.

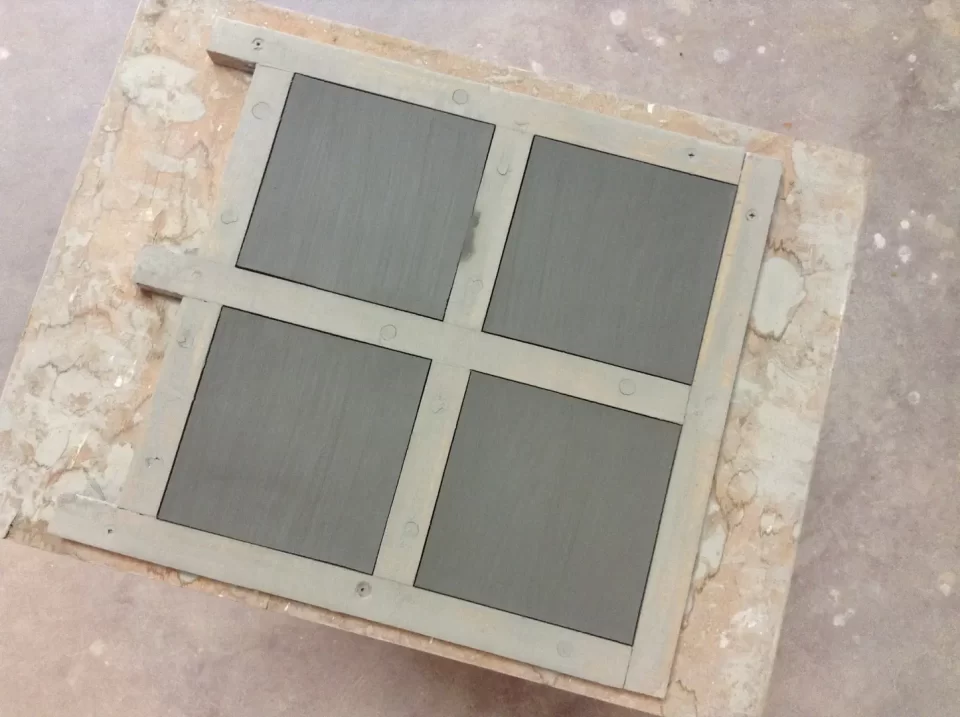

Preparing a complex installation with little lead time presented unique challenges, because as Atsonios states in his Archipelago Network video portrait, working with clay requires great patience because of its slow process and its environmentally sensitive drying time: “You cannot do more if you move faster.” The labor-intensive work also included preparing the pottery’s large kiln to fire the sculptural forms, but because there was no extra time for multiple firings, the artists had to be as precise as possible to realize the quantity of objects needed for the monastery installation. Keramea carefully calculated the exact number of objects that could fill the dimensions of the kiln, and designed the sculptural units so that they could fit together side by side like puzzle pieces, with the concave and the convex surfaces nearly touching.

In interviews with Keramea and Atsonios conducted by the author in June and October 2023, Keramea described her amazement at her collaborator’s precise formal interpretation of the kalyx-shaped fruit bowls: “It was like he had the ancient forms in his hands and his sensibility… he had such a keen understanding of his material, it was as if it was in his blood.” Atsonios also commented on how he had never considered recreating historical forms that were not handed down through his multi-generational family tradition. This was a “revelation” for him, as were the colors that Keramea chose to work with, which echoed and amplified hues in the landscape surrounding Vathy, as seen in the bottom photograph above. “Seeing Zoe’s choice of a palette was the most radical thing for me,” stated Atsonios, “and also the most inspiring for my future work.” Because the exchange involved mutual admiration and respect, the two chose to collaborate on the placement of their objects in the monastery’s spaces, where they used the architectural elements (ledges, niches, etc.) of an interior chapel space and an open air ruin.

This first collaboration served as a cornerstone for developing a regular collaborative exchange that has lasted from 1999 to today. In a conversation at a seaside taverna dinner in summer 2023, Keramea speculated on why their initial project went so smoothly. She reflected that it centered on shared values and an ethos of how to work as an artist:

We both saw something in each other that was very similar. He loved his work, and I loved mine; he was as precise with what he was doing and I was too. He was very serious and very honest and direct, and I think I was, too. So all these are qualities that are valuable. And he was very good at interpreting the forms and the shapes and that was very encouraging for me.

She also shared that the collaboration required her to adjust her typical working style. In the communal space at the pottery, she sometimes found herself caring for Atsonios’ baby daughter, stopping for shared meals, and using her polyglot talents to communicate with tourists who wandered in wanting to learn about the ceramic process as well as purchase items. This was an entirely foreign environment for an artist accustomed to working privately in a quiet and isolated urban studio–so it was personally transformative in many ways, resulting in a prolonged, intimate friendship with the entire family.

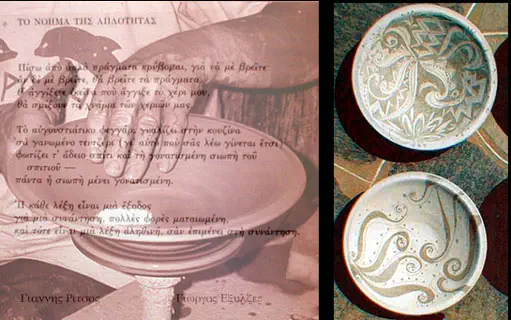

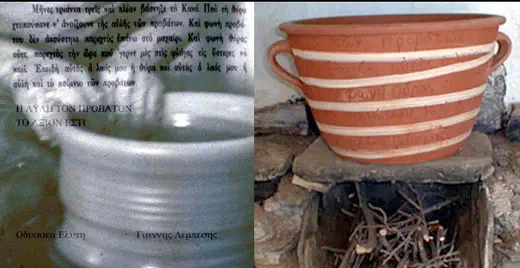

Diane Katsiaficas envisioned site-specific works for the 1999 Fyrogia show specifically in response to the monastery’s kitchen. Assigned by Krouska to collaborate with Giorgos Exylzes, she asked if he would be willing to throw domestic objects (i.e., plates, bowls and canisters– i.e., things required for both cooking and eating.) Although these were not forms he typically made in his pottery, Exylzes agreed. These ceramic forms would then serve as surfaces for inscriptions about food: texts written by Katsiaficas’ favorite Greek poets such as Yannis Ritsos, Giorgos Seferis, Maria Laina, and Jenny Mastoraki. Katsiaficas’s plan was to inscribe the Greek texts onto the ceramics made by Exylzes, so the two collaborators bridged their language gaps by reading together and discussing each poem in both Greek and English. But when she decided to include the Nobel Prize winning poet Odysseus Elytis’ “Garden of the Lambs” from Axion Esti, the collaborators realized they would need to involve another potter who could more easily throw a mastelo–a large pot for cooking lamb. Giannis Lembesis was already working with several other artists in the show, but as a mastelo master, he agreed to craft the vessel– one large enough to cook a whole lamb. As a result, Katsiaficas subsequently began spending time in the Lembesis pottery for the first time.

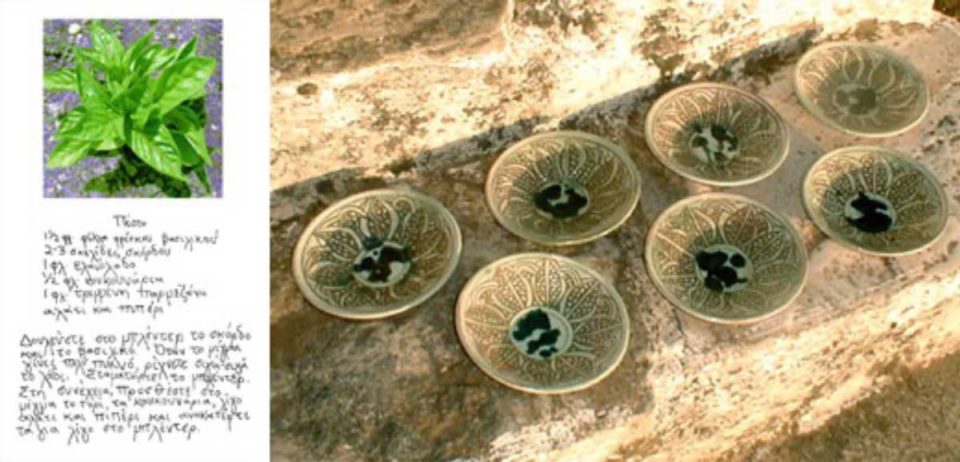

The following year, she was invited to participate in the second iteration of the Fyrogia project, but this time curator Maria Marangou assigned her to work with Nikos Raviolos, again locating the resulting work in the kitchen. Katsiaficas began researching the local culinary and natural landscape. She envisioned fabricating 11 utilitarian vessels whose surface imagery would relate to Mediterranean food recipes made with indigenous plants, such as poppy petals, dandelion leaves or capers; wine in which rosemary is added; basil dishes and strawberry leaf tea. When a large bowl was needed to hold koliva (a traditional recipe made of wheat berries and pomegranate seeds that is shared by the community in Greek Orthodox memorial services for the dead), Katsiaficas and Raviolos once again turned to Lembesis pottery, which was located next door. Giannis Lembesis was Raviolos’ uncle; he had apprenticed with him but Lembesis could not teach Raviolos how to throw large pots because of a childhood injury. To realize Katsiaficas’ vision, the three worked closely together, collectively inspired by a recent show at the Byzantine Museum in Thessaloniki (the artist had a copy of the exhibition catalogue featuring images, shapes, glazes and sgrafitto techniques from the Byzantine era.)

As Katsiaficas stated in the 2000 Fyrogia Project catalogue, “The potters magically created forms I could only draw and I drew images they felt enriched their vocabulary. While we worked to create a vessel and its surface decoration, there was an effort which none of us could effect on our own. This is the essence of collaboration.”

Listen to Katsiaficas speak about her involvement in the Fyrogia show below.

Keramea + Atsonios Pottery: Ongoing Collaborations

The presence of Keramea at the Atsonios pottery stretched well beyond her 1999 encounter and the Fyrogia exhibition—not only into the future but also the past. Her first memories of the pottery originated from an initial trip to Sifnos made with friends when she was a graduate student in 1978, inspired by her parents’ glowing recommendation based on their visit the prior year. There was not electricity nor many roads on the island at that time, so visitors typically landed by boat near the Taxiarchon Church in Vathy and then resting at the nearby Korakis taverna, which also included an inn. Keramea immediately became enchanted by the taverna’s elegant, gourd-shaped ceramic water pitchers, and inquired about their origin. The owner pointed across the bay to Atsonios Pottery, and after their meal, the travelers began the long, scenic trek along the waterfront, navigating the bay’s sand dunes and characteristic Sifnian rocks.

When she and her friends finally arrived, Antonis’ father, Mastrogiannis Atsonios, was unloading his large kiln. The visitors soon became acquainted with the workshop’s ceramic practices, purchasing a few utilitarian items as souvenirs. When they marveled at the masterful thinness of his ceramics, he told them making the edges thin allowed them to load more items onto the trade boats since they were taxed by the weight and not quantity of the pieces. Keramea never confirmed this story, suspecting it was Mastrogiannis being humble since his virtuosity had earned him a reputation as one of the best living potters in Greece at the time.

19 years later when she returned to realize the Fyrogia project, Keramea remembered the beauty of the local landscape. An avid swimmer, she requested to work at Vathy because of her memories of the village’s proximity to the sea. Only after she arrived at the Atsonios pottery and met Mastrogiannis’ son, Antonis, did she realize that this place was “home” to that memorable cerulean colored pitcher– an object that Antonis could not recall. Several years and many collaborative projects later, Keramea’s husband, James Young, serendipitously spotted one of the few remaining pitchers at the Korakis taverna.

Eventually, the owner gifted the blue-green vessel to the artist before the family shuttered the taverna. She immediately brought it back to the Atsonios family, recognizing its cultural value and honoring the grandfather’s powerful presence by augmenting their family pottery’s private collection. As such, Keramea consistently demonstrates her extraordinary capacity as an archivist. With the tenacity of a dedicated art historian, she has tracked the process of their quarter century collaboration photographically, always crediting Atsonios pottery when exhibiting their co-created works abroad and online.

Listen below to Zoe describe this fateful water pitcher and how it inadvertently led her back into the creative sphere of the Atsonios family.

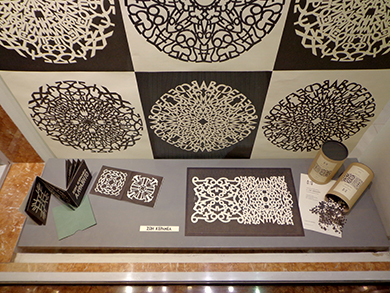

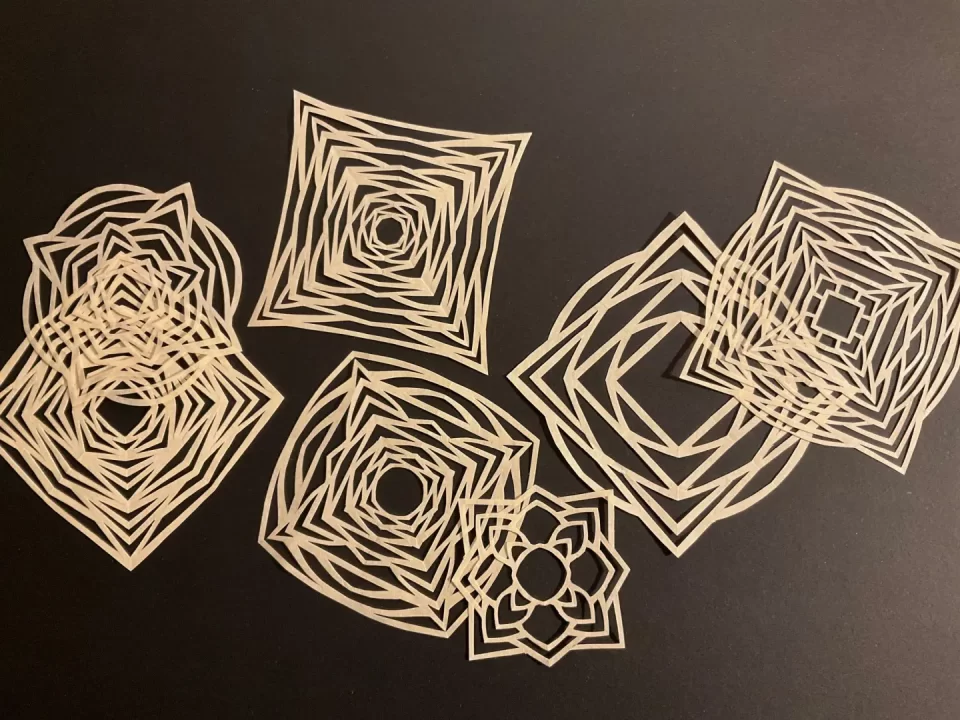

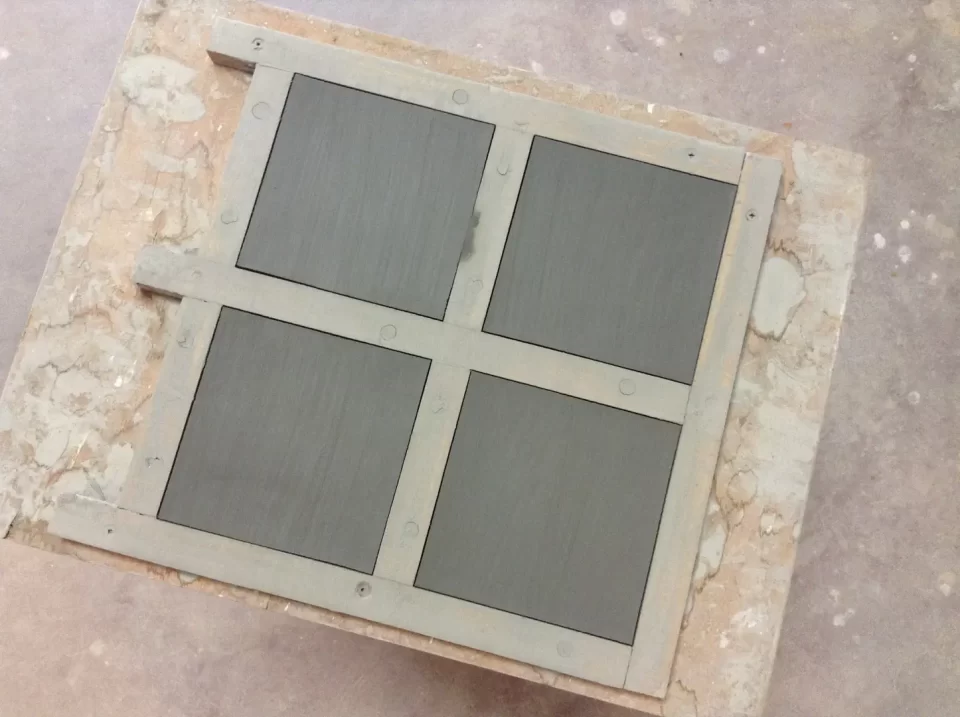

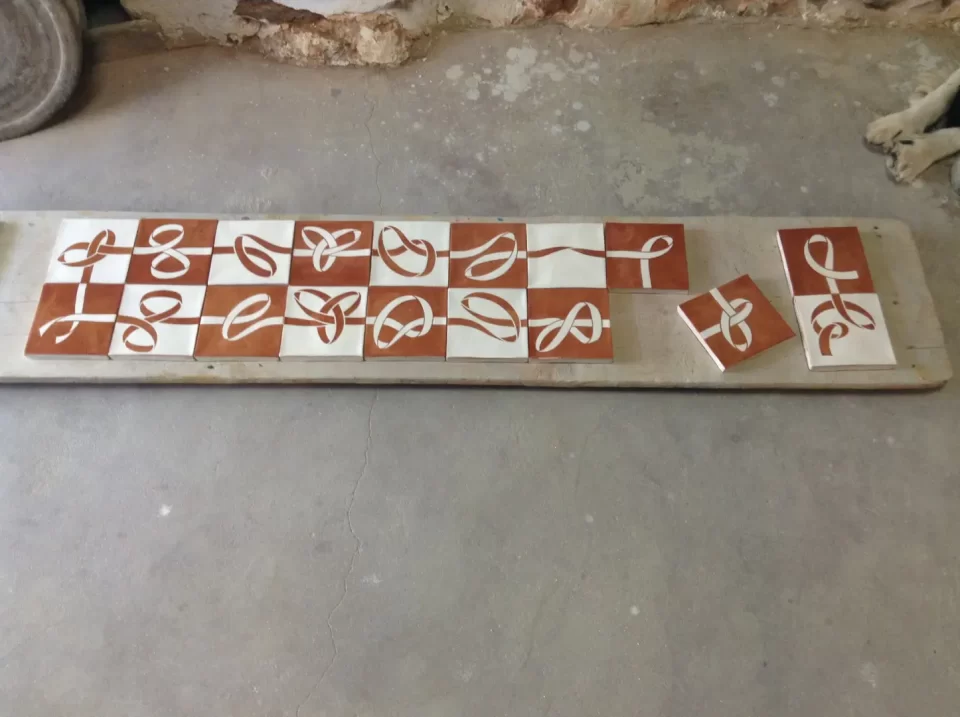

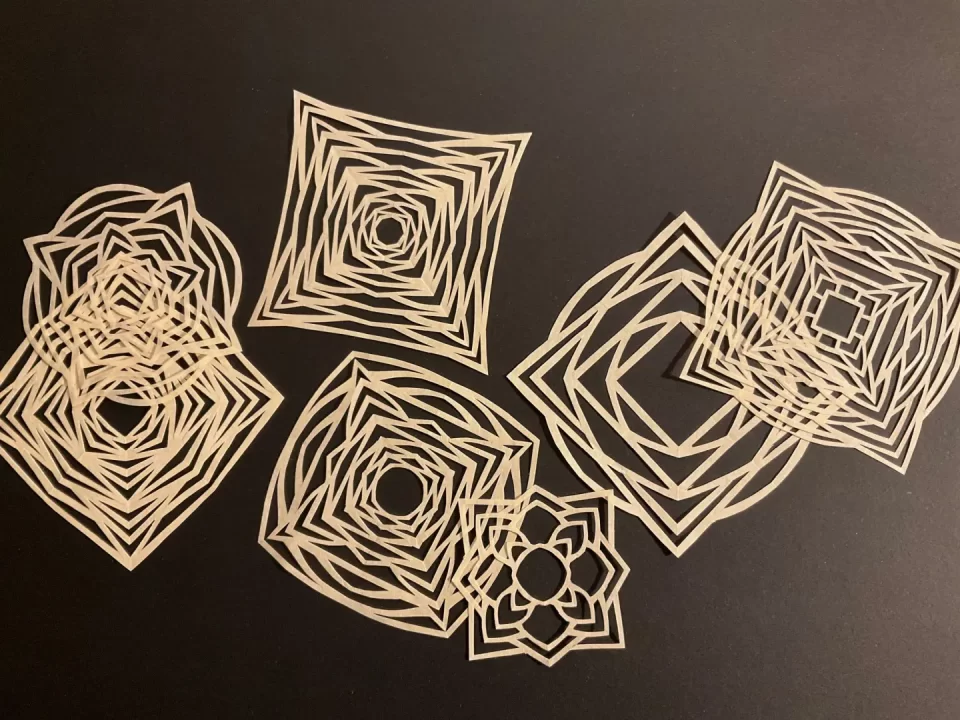

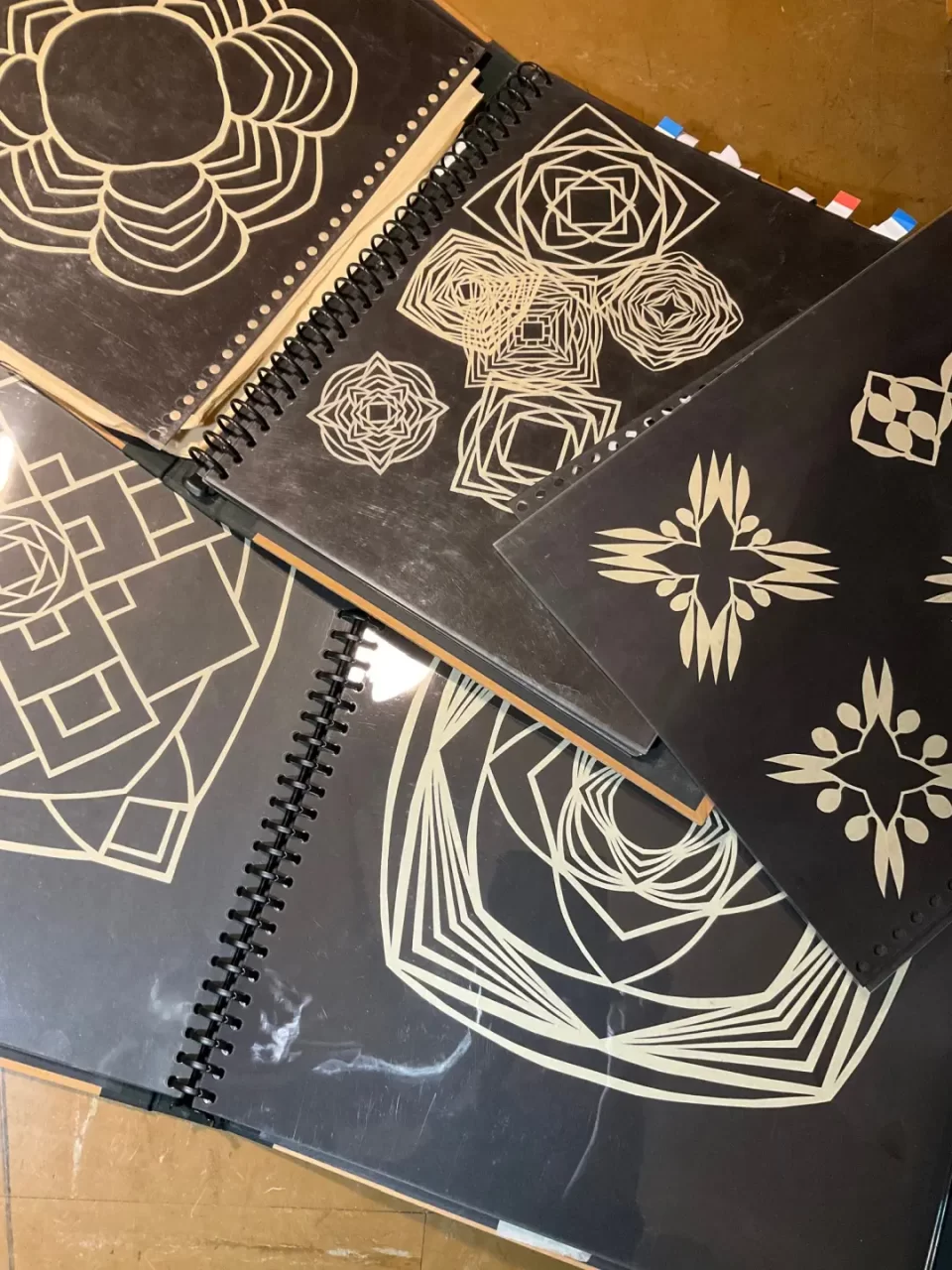

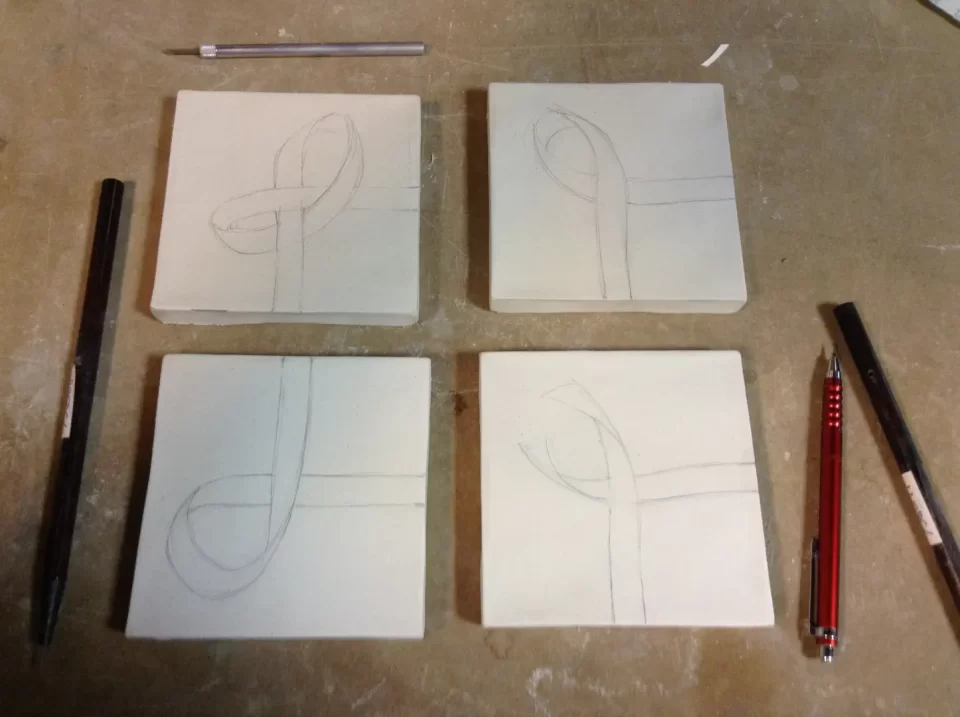

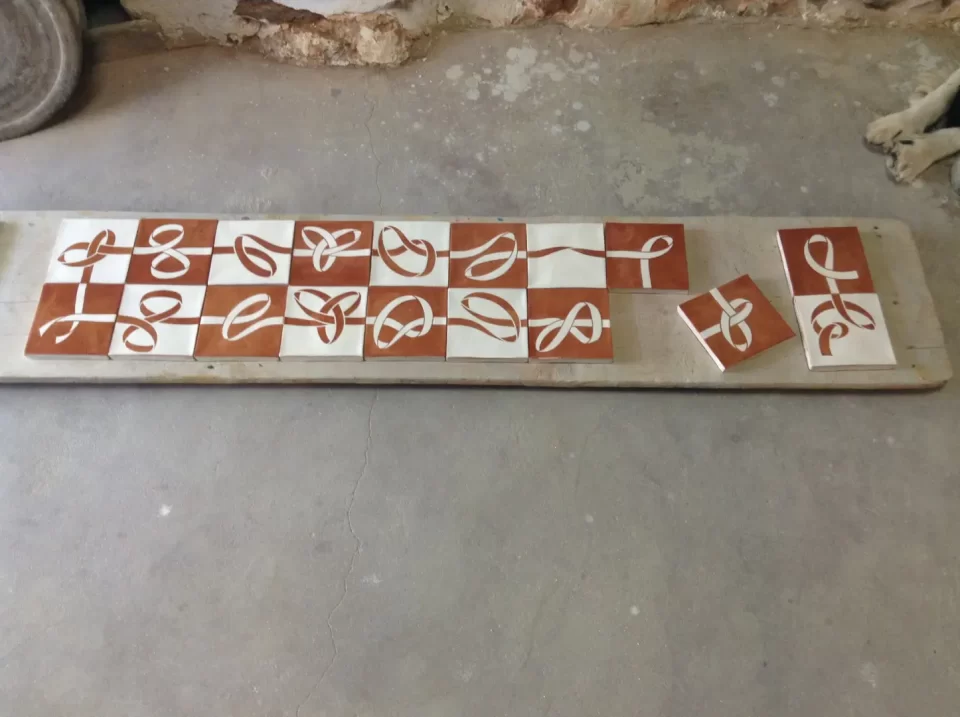

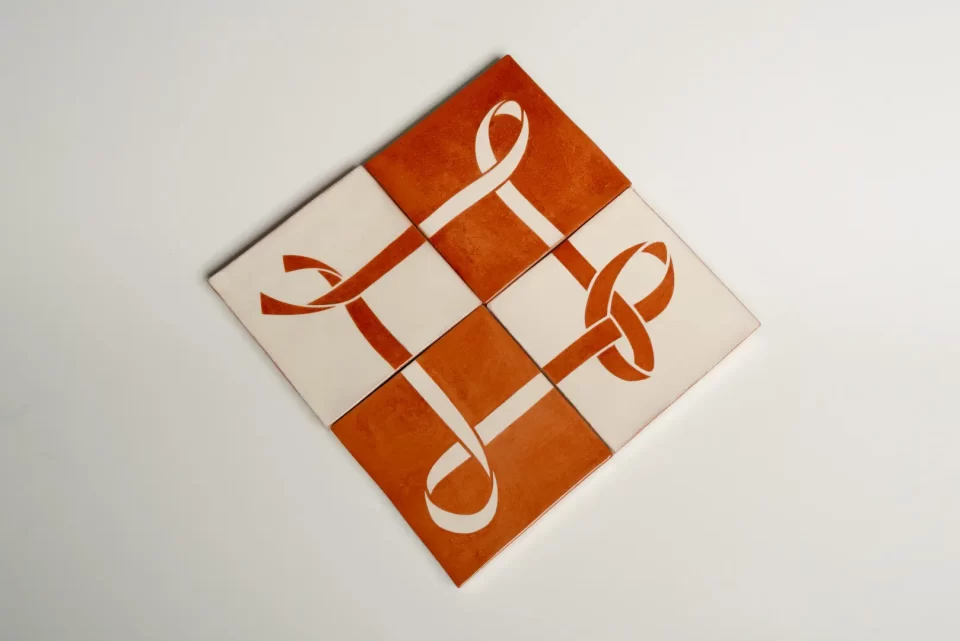

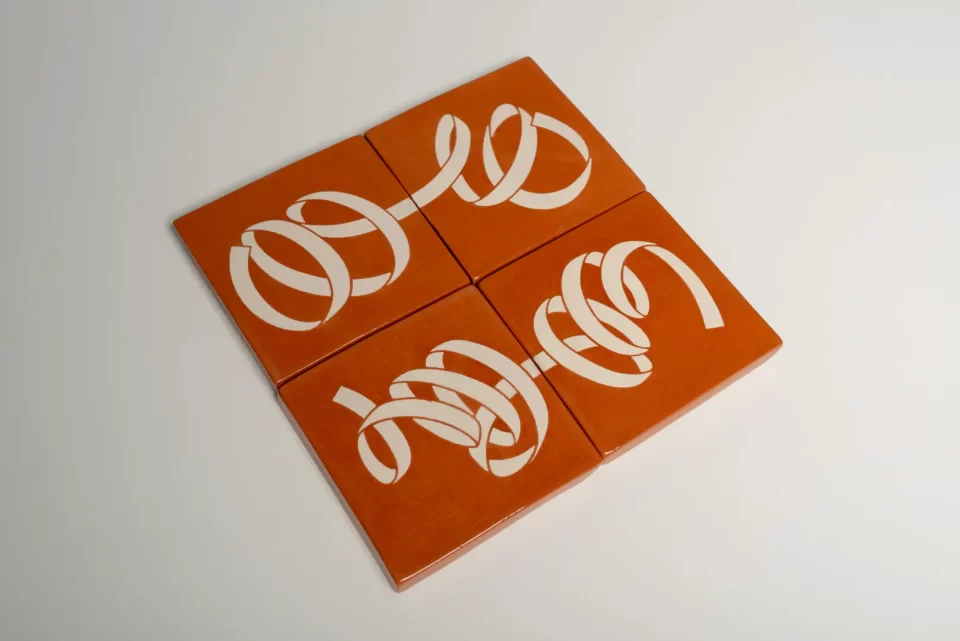

Because their Fyrogia exchange had been so rewarding, Keramea began to envision new ways for the collaboration to continue. Having now become familiar with clay as a material, she wondered if she could work with Atsonios to expand on ideas she was executing through other media. Particularly curious to discover whether she could incorporate paper cutouts to create ceramic ornamentation, she returned to Vathy in February 2000 to experiment using a “paper cut resist” technique with Antonis. The tests were successful, and since that time Keramea has returned at least once a year—only interrupted by the COVID epidemic –to apply this technique to ceramic surfaces, whether co-crafting platters or sgraffito tiles and bowls.

This labor-intensive process, which Keramea has documented extensively, involves a) positioning her hand cut paper on the damp, polished clay surfaces; b) wetting the cutouts; c) applying slip; and then d) removing the paper cutout after the slip has dried. This final step includes painstakingly scraping the slip residue away from the edges of the design with an X-Acto knife before firing. In a second approach she co-produces sgraffito tiles and bowls, this time drawing directly on the surface of the slip and scratching the relief drawing. What ultimately appears on the ochre or white clay surface is typically a geometric mandala or dynamic linear pattern–imagery related to her previous projects.

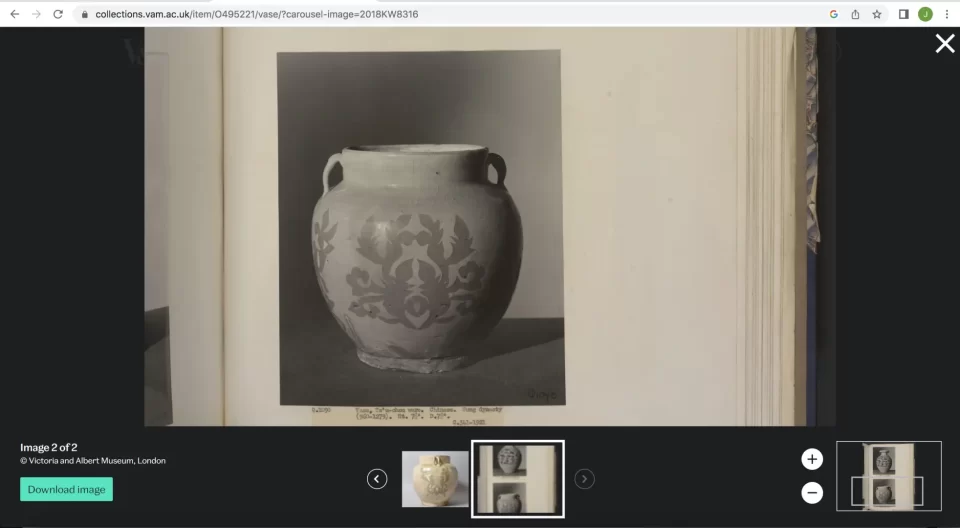

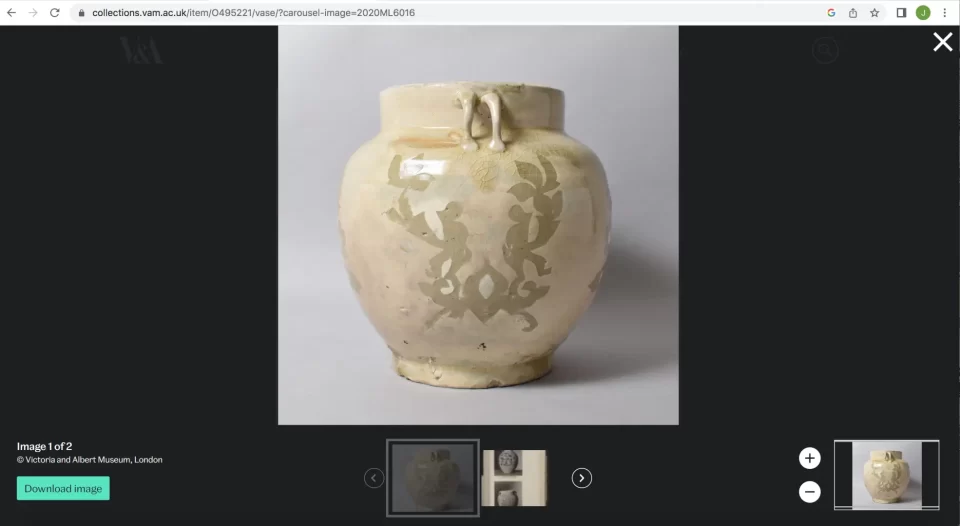

Curious to know who may have used a similar technique in the past, Keramea began researching in libraries and discovered that the Chinese did, in fact, invent this technique, frequently abandoning and re-inventing it to make it less laborious. While she has never seen an actual Chinese paper-cut resist vessel, she did locate an image in a book by Nigel Wood entitled Chinese Glazes: Their Origins, Chemistry and Recreation (University of Pennsylvania Press, 1999), which led Keramea to locate more images in the digital archive of London’s Victoria and Albert Museum. Like Atsonios’s ancestral memory of the calyx form unconsciously harbored in his hands, it was if Keramea’s dedication to the craft of papercutting unwittingly allowed her to channel its cross-cultural ancestry.

Listen below to Zoe describe her collaborative experience with Atsonios pottery, from an October 2023 interview with the author recorded over dinner at a taverna in Platys Gialos.

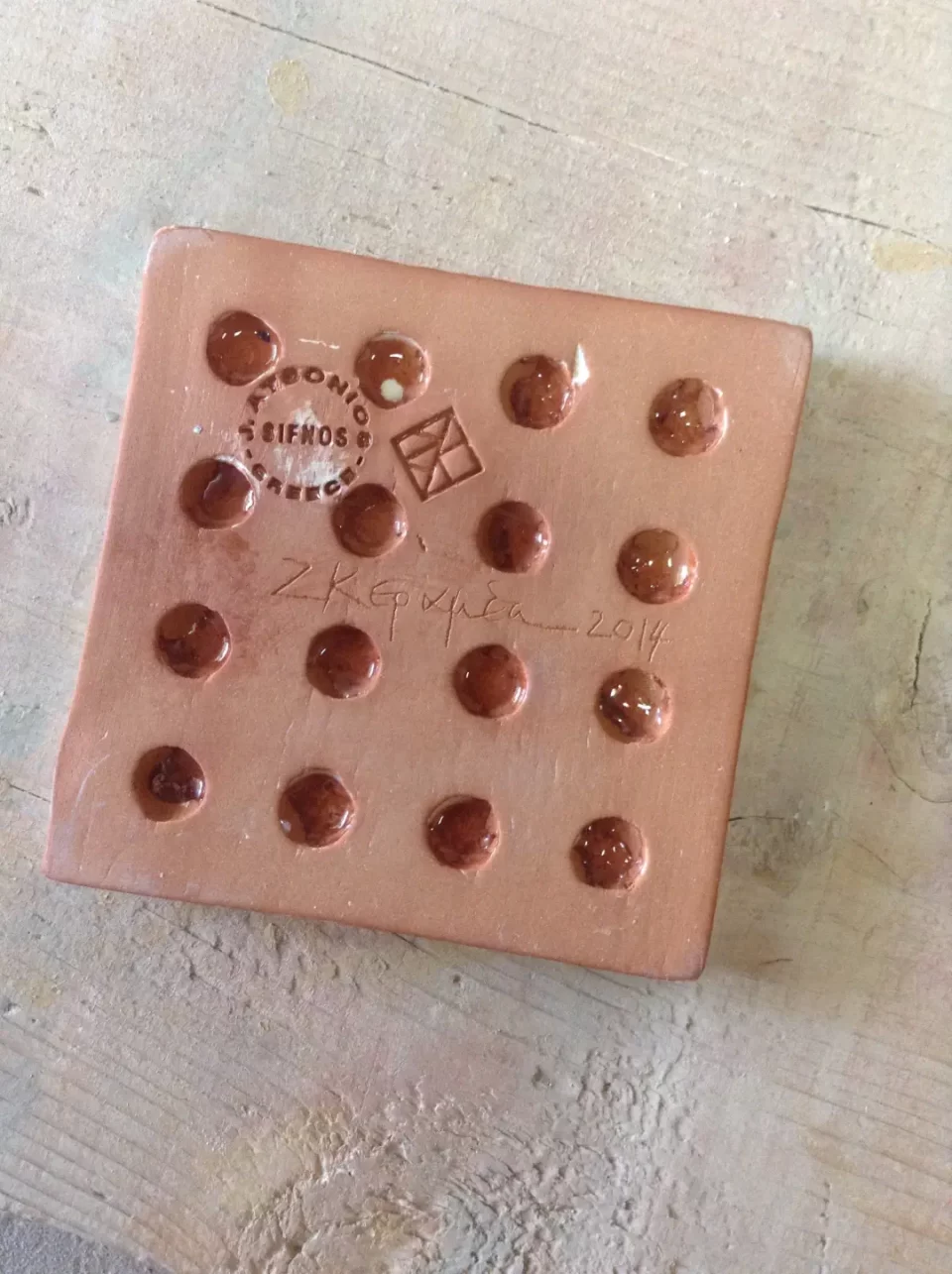

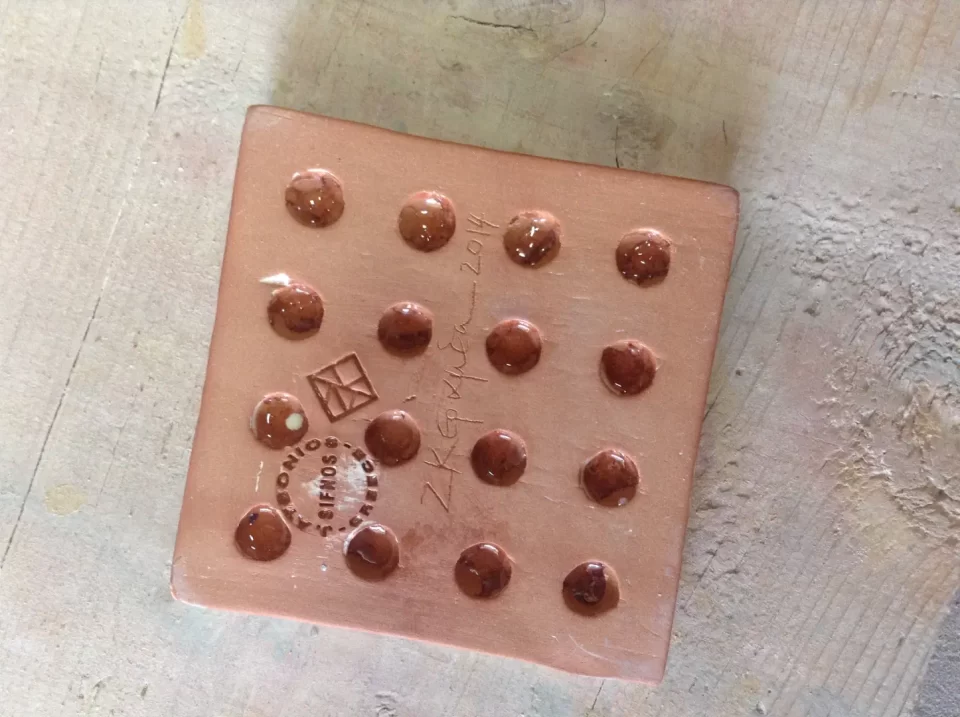

On a practical level, the terms of Keramea and Atsonios’s the transactional agreement were made clear from the start: she would pay him to throw the ceramic forms she designed on paper, and she would then ornament the surfaces after he applied the traditional white slip (“baidanas”). This compensated for the cost of his labor and materials, paying full retail price. After firing the objects, Keramea would then keep them for her own private collection, keeping potential profits from any future sale she might arrange. However, since they conducted their making process together, the Atsonios pottery—now consisting of both Antonis and his gifted son Giannis– could replicate or improvise on Keramea’s forms and glaze techniques, without needing to consult the artist. In other words, their co-creations become starting points for some of the pottery’s future production. All objects that arose from their collaborations are stamped with both Kerameas’ and the Atsonios’s seals to acknowledge their hybrid origin, but sales of works subsequently produced by Antonis or Giannis would solely benefit the Atsonios pottery.

In essence, the ideas, forms, and colors that arose from these artist/craftsperson collaborations became understood as shared intellectual property. For example, the unique double dipped bottles from the Fyrogia show—with their unglazed center circle that functions as a hand-hold– immediately sold out as early as 1999, and remain in high demand. The kalyx-shaped fruit bowls have also consistently proven to be a popular item among buyers, so the pottery continues to produce and sell these items twenty five years after their initial conception. Also, when Keramea receives a commission for co-produced objects that will become property of the client (e.g., ceramics made for the nearby Elies resort hotel or a family’s religious event), she determines the prices–which are considerably higher than pottery rates because of her status as an internationally renowned contemporary artist. In such cases, she splits the sale price evenly with Atsonios. From 1999 to present, they have co-created more than 500 ceramic pieces together. This economic exchange has proven to be a “win-win” situation for everyone involved, and has allowed both parties to push their previous creative boundaries.

In the Archipelago Network video portrait of Antonis and his son Giannis, Antonis reflects on the profound influence contemporary artists like Keramea have had on Sifnian potteries: “Artists have boosted our craft tremendously. Along with tradition, there is that element, too. It’s a line of work that never ends.” In a similarly spirited comment made during a conversation in summer 2023, he theorized that the history of his pottery’s production falls into three distinct periods:

1) when family traditions/ techniques were handed intergenerationally and replicated as such;

2) the post-WWII governmental intervention by EOEX (acronym for the National Organization of Greek Handcrafts), a program intended to boost Greece’s waning handicraft production by encouraging potteries to diversify their repertoire by crafting smaller utilitarian objects such as cups, plates, etc.

3) collaborative interactions with contemporary artists such as those initiated through the 1999 Fyrogia project, now independently sustained by Keramea through her ongoing aesthetic and economic exchanges.

Given the primacy of Zoe’s contribution to Atsonios pottery’s history, as well as their longstanding personal friendship, it is no wonder that the exchanges between the artist and the Atsonios family extend beyond the days she and her husband James spend each year in Vathy. Since they began collaborating, the Atsonios family has visited Keramea in Athens, where they compared aesthetic responses to collections, for example in the Keramikos Museum, the Byzantine Museum, Psaropoulos Museum of Traditional Pottery and even Sektor 30, a collective workshop space in Neos Kosmos founded by artists Maria Efstathiou and Ilias Koen. Sektor 30 provided an example of another way to establish ceramics, casting and wood workshops for artists, designers and craftspeople. Because of such visits, ideas that inform craft practices continue to spark, both on the island and beyond.

Katsiaficas + the Lembesis Pottery: Ongoing Collaborations

Diane Katsiaficas developed a different model of ongoing collaboration with the Lembesis pottery: she became embedded in the daily life of the studio, volunteering long hours to paint their ceramic forms whenever she visits the island, several times per year, for days or weeks on end. By the time she completed her second Fyrogia exhibition, Katsiaficas had established such a deep connection with both Giannis and Kateh Lembesis that they invited her to become part of their production team. Recounting that moment in late 2000, she said, “Yannis said to me, look, you love to draw on these, and I like what you’re doing. And Kyria Kateh and I enjoyed each other’s company… We got along like a house on fire… And so I would just start coming.”

Shifting status from an outsider/tourist to an insider/local, Katsiaficas offered her improvisatory artistic methods, pedagogical talents, material resources and deep knowledge of both art history and contemporary art in exchange for becoming an extended family member, both on a professional and personal level. Katsiaficas now resides in the Lembesis family’s “spitaki” when she is on the island—a small house not far from the workshop–and is one of the godmothers of Nikos and Maria’s youngest son Chrysanthos. As Katsiaficas asserted, “This was not just about going and making designs. This about expanding a family.”

Listen below to Katsiaficas tell the story of her husband Norman’s 90th birthday party, for which the Lembesis family gifted the couple 150 cups, and surprised them with a Lembesis family visit to Rafina to sing and share in the celebration.

Through her creative dialogue and artistic contributions to the pottery, she became recognized as an essential force in its evolution. In his Archipelago Network video portrait, Giannis’ son, Nikos Lembesis, spoke of the 1999 arrival of “Ms. Diane”:

That’s where the whole history of the shop started. Painting on the pottery, etc. We were also painting before this, but we were doing more traditional things with white decorations on red clay or etchings on the flaros or other objects. . . And when Diane showed up, with her experience, we gradually changed this, adding colors, and began to develop. Grandma evolved a huge amount… she created a world of her own with little birds, trees, flowers, fish. These patterns that are now very characteristic of us are hers, so to speak. . . she had a huge imagination.

Just as she had done during the Fyrogia projects, Katsiaficas suggested the Lembesis family consider using colored glazes. She exposed them to images of Byzantine era ceramics and brought cobalt oxide, iron oxide and manganese oxide glazes to the island from Athens for everyone to experiment with. Seeing their traditional patterns, she provided a wider context by sharing a copy of the Dictionary of Universal Signs and Symbols, which excited Kyria Kateh. She also brought Kyria Kateh Sumi brushes purchased during travels in the US and China, with which the elderly matriarch was thrilled to experiment. Along with material contributions, Katsiaficas introduced a large range of designs into the pottery’s repertoire, including small pomegranates that were growing in the Kyria Kateh’s garden, red poppies that filled local fields in springtime, lilies derived from the Minoan frescos on the Cycladic island of Santorini, shrimp, jellyfish, lobsters, snakes, octopi, evil eyes, and all sizes of fish, among other motifs.

Fish especially interested the artist because she had fished commercially while living in the U.S. Pacific northwestern city of Seattle, an experience that made her keen to study the “catch of the day” that Nikos Lembesis, a free-diver, would haul in for the family meals. Together the workshop team looked at 4th Century BC platters, and Katsiaficas would point out that these depictions of fish were not static frontal images but mimicked how the creatures might swim around on a clay structure. As she had done for her art students at the university, she also demonstrated how to paint the negative space, and not only the object itself, resulting in the black and white fishes. All these images and techniques– from loose brushwork to intricate sgraffito–then became collective starting points for everyone working in the pottery. Like jazz musicians, they would improvise on each other’s visual scores, responding to the “call” of one another’s unique sensibility until they ended up with what Nikos describes in his Archipelago Network video portrait as “the mix.”

See this 2007 video of Kateh making a sgraffito fish bowl, and the below photo gallery, for examples of Kateh’s designs.

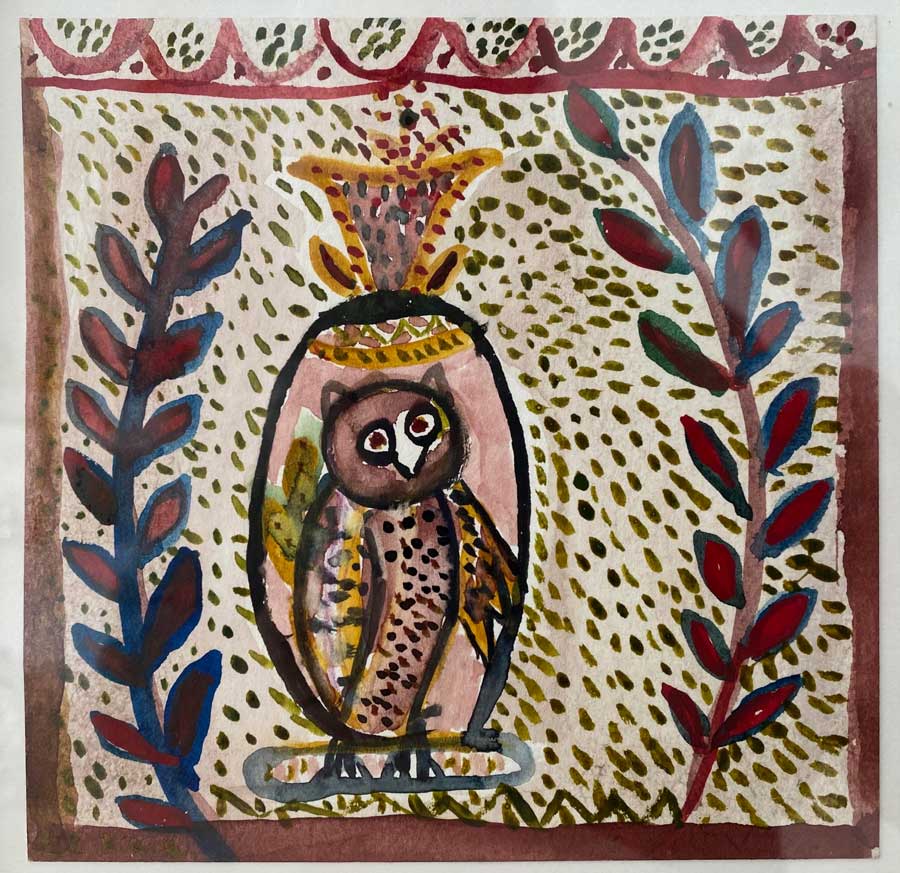

Katsiaficas and Kateh inspired each other tremendously, and playfully bantered with a brush in hand, sometimes going so far as painting together on the same object. As the artist recounted, “Kyria Kateh was doing bugs with little feet, so I started doing fish on skateboards because there was one local guy who had one, and we would laugh… When I took her to the Benaki Museum in Athens, she looked at the owls that were painted on cups, and she began painting her own versions. So that’s the give and take of just being playful…”

The two artist friends cared for one another in various ways. In 2009 Kateh Lembesis had severely strained her back and was in need of physical therapy, so Katsiaficas and her husband invited her to come to Rafina to stay at their home so she could undergo medical care. Her physical therapy lasted for two weeks, so when she wasn’t getting treatments, Diane suggested she try painting on acid free paper with her sumi brushes and fine Schminke watercolors. It was the first time Kateh had experienced the immediacy of seeing bright colors on absorbent paper, since with glazing there are many factors that can make the composition unpredictable. This launched her love of painting on paper, which she continued until the end of her life. At age 82, she had her first one-person exhibition on Sifnos, which nearly sold out due to her popularity in the community and the attention she had garnered from visitors.

Listen below to Diane Katsiaficas describe the period when Kateh Lembesis began painting on paper.

Katsiaficas also arranged for other members of the family to travel further in search of artistic exchange. As early as February 2004, Giannis and his two eldest sons, Manolis and Nikos, visited the University of Minnesota where she taught. As Katsiaficas states on her website,

Students and faculty were thrilled by the Lembesis’ facility and productivity in throwing traditional forms, especially the ease with which they adapted to a variety of clays which, up until that point, they had never encountered. Everyone joined in the process of sgrafittoing on pots. The Lembesis enjoyed the interaction. . .especially their introduction to the wealth of information regarding glazing processes that ceramics Professor Tom Lane generously offered.

This transatlantic exchange continued: one year later, Professor Lane visited Sifnos with one of his graduate students, Nick Darcourt, and shot the previously referenced documentary video of the Lembesis family at work in their pottery, creating a broader cultural context for English-speaking viewers. In 2006 Nikos returned to the University of Minnesota art department and as a result of what he learned during this visit, he initiated the use of lead free glaze to all ceramic work in the pottery. Finally, in 2017 Giannis visited again as a Visiting Artist for 10 days to demonstrate the creation of traditional Sifniot ceramics. The Lembesis-Katsiaficas collaboration continues to inspire new forms of creative production. In 2023, Kelsey Bosch, a former University of Minnesota student of Diane’s who had heard much about the Lembesis’ visit to the United States, found a new way to engage with the pottery. As an artist interested in pscyogeographical soundscapes and the first Artist-in-Residence at Katsiaficas’ home in Rafina, she created an improvisational sound piece with four players–including Bosch and Katsiaficas–entitled, “Sifnian Echea”. Referencing the sounding vases or acoustic jars typically found in walls, ceilings or floors, Bosch explains, “The fine craftsmanship of Lembesis pottery produces a ringing sound similar to crystal when struck; each piece has a unique pitch.” This enchanting piece echoes the playfulness exchanged between Katsiaficas and Kyria Kateh, and demonstrates how ceramics can inspire a range of multidisciplinary artists.

Needless to say, these sustained dialogues not only widened all parties’ worldviews, but deepened their understanding of what global artistic collaboration can engender.

Conclusion: Female Hands at Work

By experiencing their stories and witnessing a small sample of the works produced by these three artists, we can recognize the need to research and celebrate the vast influence women have had in shaping the ceramic tradition on Sifnos. By framing local potteries as collective enterprises and intimate spaces of creative exchange-rather than simply manifestations of a patriarchal craft heritage—it is possible to discover the layered complexity of this dynamic, UNESCO-sanctioned site of intangible cultural tradition.

Simultaneously, this interactive essay is meant to provide an argument for future artist-in-residency opportunities on the island. The examples of both Keramea and Katsiaficas’ ongoing activities as artists on Sifnos speak to the rich dialogue and learning that can take place when diverse artists—especially those from divergent professional, personal and geographic worlds– cultivate sustained collaborative exchanges with local craftspeople. The potteries of Sifnos may then become a kind of “home away from home.”

As French philosopher Gaston Bachelard notes in his book The Poetics of Space, a house—or by extension a family studio space– “is a tool with which to confront the cosmos. It helps us to say, ‘I am an inhabitant of this world, in spite of the world.’” The Atsonios and Lembesis potteries have also proven to be these kinds of bold professional and domestic spaces, acting as a microcosmic representation that holds and triggers memory. They provide much needed links between generations and historical periods. Through cross-cultural collaborations such as those of Keramea and Katsiaficas, these potteries demonstrate how diverse cultures may inform each other and produce innovative fusions.

It has been my pleasure and privilege gaining access to these worlds, and hope that with the promise of a Ceramic Museum and School for Ceramics in Sifnos’s future, international and local governments, cultural foundations and individuals will support establishing more artist-in-residence opportunities on the island.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Jacob Moe and the staff of the Archipelago Network for undertaking this ambitious and culturally significant project, and for the invitation to respond to their newly formed archive. Thanks, too, to Sifnaika Konakia Hotel for their warm hospitality while I was researching on the island. I am especially appreciative of the time and enthusiastic participation of Zoe Keramea and Diane Katsiaficas, both of whom welcomed me into their homes and families, sharing intimate insights about their personal and professional lives. They are artists whom I deeply admire. Finally, my sincere gratitude goes to the Atsonios and Lembesis families, whose talents are inspiring, and whose warmth and generosity manifested in delicious shared meals (mastelo included!), conversations and gaining access to their family photo archives. Thanks especially to Maria Maiopoulou and Nikos Lembesis for sharing their computer files, which were invaluable. These family potteries are the treasures of Sifnos, and I look forward to sustaining a friendship with them in the years ahead.